At the Collins Park Water Treatment Plant, chemists and engineers transform Lake Erie water into drinking water for nearly 500,000 people. Fish are removed and contaminants are purged — including enemy No. 1, the toxin microcystin that comes from the blue-green algae clogging the lake. It was concern surrounding those microcystins that caused a “no-drink” water advisory for the Toledo region Aug. 2-4.

Soon after, the Collins Park Water Treatment Plant came under scrutiny when the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency claimed it had plans to take over operations if the city failed to improve the plant’s conditions. It seemed the 73-year-old plant was to take at least partial blame for Mayor D. Michael Collins’ administration’s failure to protect the city’s drinking water.

But city officials refute that, saying it was a harmful algal bloom at the water intake site, not conditions at the plant, that caused the advisory.

Collins Park Water Treatment Plant Administrator Andrew McClure, photographed Sept. 3, 2014. Toledo Free Press photo and cover photo by Christie Materni

“There’s a perception that this is a 70-year-old plant on its last leg,” said Andrew McClure, the Collins Park Water Treatment Plant administrator. That couldn’t be further from the truth, he said.

RELATED: Algae crisis is ‘game changer’ for region’s water supply

That’s why McClure and program manager Warren Henry wanted to give the media a tour inside the plant, built in 1941, to show reporters that walls are not falling down, paint isn’t peeling and all filters and pumps are working properly. They want Toledoans to know their tax dollars are hard at work bringing safe drinking water to their taps.

“We want to be good stewards of public funds,” Henry said Aug. 28.

The plant is slated to undergo millions of dollars of repairs and an expansion. Officials are looking into ways to combat the algae, but wouldn’t specify what new technology they would use. Overall, they were optimistic that the plant would be operating for many years to come.

Treatment process

In Lake Erie, raw water enters what’s called an intake crib through 16 underwater ports. The intake crib is 83 feet in diameter, 24 feet below the surface of the lake and two and a half miles offshore.

The water travels from there to a pump, which sends the water eight miles to the Collins Park Water Treatment Plant. The water has been in pipes from Lake Erie up until it reaches the chemical feed room at the plant.

Here, chemicals are added, including activated carbon, aluminum sulfate, potassium permanganate, chlorine and fluoride to soften the water and remove contaminants.

From the chemical feed room, the water flows to the flocculation and sedimentation rooms. Here, residue is removed as large particles bond and fall to the bottom of the basin and fine material that doesn’t settle is filtered out. At this point, the water looks good enough to drink but isn’t safe yet, Henry said.

The water, which had been open to the air since entering the plant, now flows into pipes below ground level. This piping is 30-50 years old, Henry said, and is slated for upgrades.

The water flows from the pipes to water reservoirs, then high-service pumps send it through the distribution system and finally to customers’ faucets.

The administrators of the system call it a “barrier” system, in which several safeguards are put in place to protect the water, beginning with the chemicals added at the low-service pumping station where contaminants such as fish are removed to the high -service pumping station at the end of the line where filters continue to remove contaminates before pumps move it to customers.

Cost of repairs, expansion

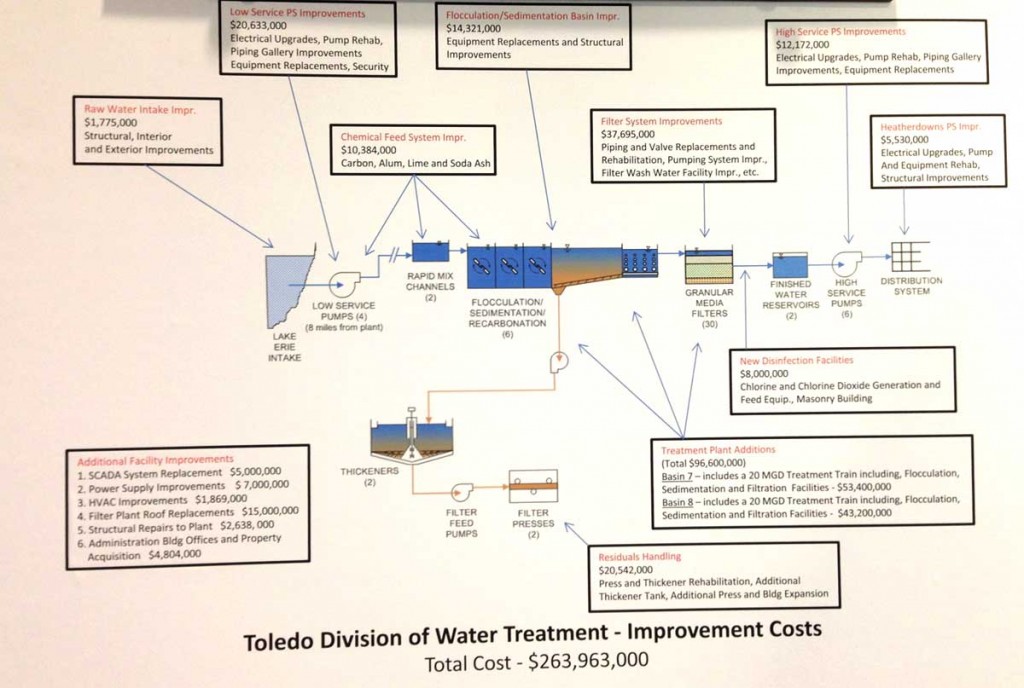

Administrators during the tour discussed “improvement costs” to the plant, totaling about $264 million over five years. Some of those expenditures include $1.7 million for structural repairs at the intake crib, about $30 million for pump upgrades, $37 million for filtration improvements and about $100 million in basin upgrades.

“It’s easy to throw away the old,” Henry said. “Just because something has aged doesn’t mean you throw it away. Repairs can last a long time.”

Improvement costs for Collin Park Water Treatment Plant. Click to enlarge. Photo courtesy City of Toledo.

Media members asked whether it would be more cost-effective to build a brand-new facility. Henry likened the plant to an automobile.

“I don’t believe in buying a new car because it needs a new set of brakes,” he said.

During the tour, it was evident that the building was old but in good repair, at least cosmetically. The ceiling that hangs over the open drinking water looked clean and fresh with shiny gray paint. The new roof has been worked on in sections and is nearing completion, McClure said.

The age of the structure was apparent in art deco filtration control panels, which are no longer in use.

“We’re rehabbing everything and with the new addition, we’ll get another 70 years,” Henry said. “I have no hesitation saying this at all.”

McClure and Henry discussed the expansion while standing on the location of the planned site, saying the “redundant expansion” will give them a potential 160-million-gallon capacity. Currently, they are using a 120-million-gallon system — six treatment basins, each with a 20-million-gallon capacity.

The expansion will allow portions of the plant to be shut down for heavy maintenance instead of trying to make repairs in a working section of the plant or having to wait until winter when water use is lower, McClure said.

The repairs will be phased in within the next four years and the expansion is about two years out, they said.

“We’ve operated this facility successfully for 70 years,” Henry said. “We’re the only plant for the area.”

In other costs, the treatment plant is paying about $1.7 million more for chemical treatments since the algae crisis, administrators said. They have a $3 million to $4 million budget for chemicals.

Administrators say they do not know how much they’re going to use because they can’t predict the condition of the lake water. The chemical budget for this past year was $4.7 million, which won’t change despite the conditions of the lake, because they have a three-year contract with suppliers.

The algae

Administrators are looking to technology to deal with the algae.

They said there are a number of different options they could use at the plant to protect the water against microcystin, including membranes, ozone or granulated carbon. They are looking at augmenting the chemical and/or the filtration process. Henry called these options “barriers,” and said they are not just concerned about the microcystin but about all contaminants.

“We hope to have another barrier by next year,” Henry said.

In the meantime, McClure said the plant, with its chemists, engineers and 30 licensed operators, is working in partnership with the Ohio EPA.

“Everyone has their role to play and we’re working hand-in-hand,” he said.