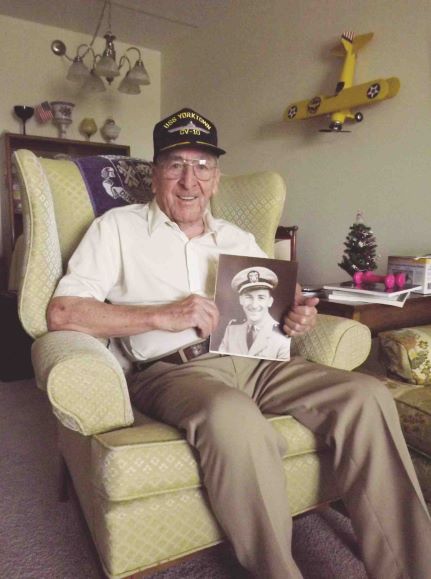

Toledoan Alex Rapp made it through World War II unscathed, but not for lack of action.

The Naval aviator, now 94, was stationed on the USS Yorktown and flew a Grumman TBF.

“That was a rugged airplane. It could take an awful beating,” Rapp said. “Our job was to sink ships, blow up hangars, blow up airfields, anything we could destroy. We were all over that ocean. I estimate I killed about 2,000 Japanese myself. It’s a big ocean. They had lots of places and we bombed them all.”

One place in particular he recalls is Truk Lagoon, now known as Chuuk Lagoon, in the Caroline Islands.

“Truk was a big installation in the middle of the Pacific,” Rapp said. “It made our Pearl Harbor look like a little hole in the wall. It was a powerful place. We attacked that four times. Oh boy, that was a dangerous place.”

Although never injured, Rapp had several close calls.

One came when he was lined up for takeoff too close to the end of the carrier’s runway.

“We were supporting landings at Saipan and I was the first of six planes to take off from the carrier, just after dawn. I got down to the end of the deck and I only had 69 knots. It takes 72 knots to fly, so I’m sinking down right to the ocean,” Rapp said. “It takes patience and nerve just to hold everything steady and I finally got that plane up in the air. The dangerous part was I had depth charges. If I would have hit the water, they would have blown me right up. When I came back, the flight officer came up to me and said, ‘I apologize to you. I only gave you 300 feet for takeoff and it should have been 330 feet.’ I could have punched him in the nose.”

Another time, Rapp left with a group of 150 pilots on a bombing mission to Kwajalein, an atoll in the Marshall Islands, but when they arrived at the specified location, the intended target was nowhere in sight. They soon located the ship further down the coast, but getting there used extra fuel.

“I got right down on the water, right at the ship, dropped the bomb and went over,” Rapp said. “I could see a guy shooting at me from the stern of the ship and, when I went over, why, he hit me underneath and blew a hole in the plane. But that was the easy part.”

Meanwhile, the group of carriers the planes had taken off from came under attack by the Japanese and radioed to say they were moving out. Already low on fuel from the miscalculated bombing location, the pilots would now have farther to fly to make it back.

“We were expendable,” Rapp said. “They left us, but we finally caught up with them. We all landed while the Japanese were attacking. We got aboard the carrier and had to find places to hide. I had 23 gallons of gasoline left and these other guys had less. They were patting me on the back saying, ‘Boy, you were terrific to save all that gas.’ So we made it back, but that was a rough day.”

TBFs were designed to carry torpedoes, but the pilots used bombs instead because it was safer. To minimize their chances of being shot down, the pilots would dive at more than 300 mph toward their targets.

“You’d try to get as fast as you could go,” Rapp said. “With torpedoes, you had to fly low and slow, but with bombs, you could go in fast and still have a lot of speed to get out of there.”

Rapp recalled dropping a torpedo only once, near Saipan.

“There were nine of us loaded with torpedoes and we chased this destroyer and caught up with it and attacked it,” Rapp said. “Five planes attacked from the port side and four planes came in from the starboard side and we bracketed that ship. They hit at almost the same time and it was the biggest explosion I’d ever seen. Just like that, it disappeared.”

One time, the pilots loaded their planes not with bombs or torpedoes, but with food. After helping Marines take control of Eneweitok Atoll in the Marshall Islands, Rapp’s ship had moved on to another mission when they got word the Marines had run out of supplies.

“We were about 1,000 miles away, but we sailed back there and loaded up 11 planes and brought them 11 tons of food,” Rapp said. “The runway was made out of coral and it was just as white as can be. I was flying in and thought to myself, ‘Boy, this is beautiful. I’ve never seen anything so beautiful.’ The food came from our ship. We ate a lot of rice after that.”

Rapp was the oldest of eight siblings. All four of his younger brothers also served in the military.

“We were all over the world,” Rapp said. “It must have been tough on our parents, all the boys being gone. I think about it once in a while, but my mother and father were tough people. They were immigrants from Europe.”

His brother Gene was drafted into the Army and was at Pearl Harbor when it was attacked.

“He said it was terrible and we were not prepared for anything,” Rapp said. “He was at Hickam Field and the Japanese shot up all the planes that were on the runways.”

Knowing they would soon be drafted, Rapp and another brother, Joseph, joined up.

Joseph served in the Army and Air Force with a B-29 photographic intelligence unit.

“His group had more pictures and knew more about Japan than the Japanese did,” Rapp said.

Rapp’s two youngest brothers later served during the Korean War.