To walk around Fifth Third Field is to walk amongst the names of Toledo baseball lore.

Before leading the New York Yankees to five consecutive World series titles in the 1940s and ’50s, Casey Stengel cut his managerial teeth in Toledo, leading the 1927 Mud Hens to the city’s first league championship. Moses Fleetwood Walker broke ground by becoming the first African-American to play in the major leagues as a member of the 1884 Toledo Blue stockings. Ned Skeldon, Jerome Schmit and Henry Morse broke ground more literally — spearheading the transformation of an old Maumee racetrack into a ballpark that would bring baseball back to Toledo. Gene Cook was the visionary responsible for the Mud Hens references on “M*A*S*H” as well as an early advocate of the team’s move to Fifth Third Field.

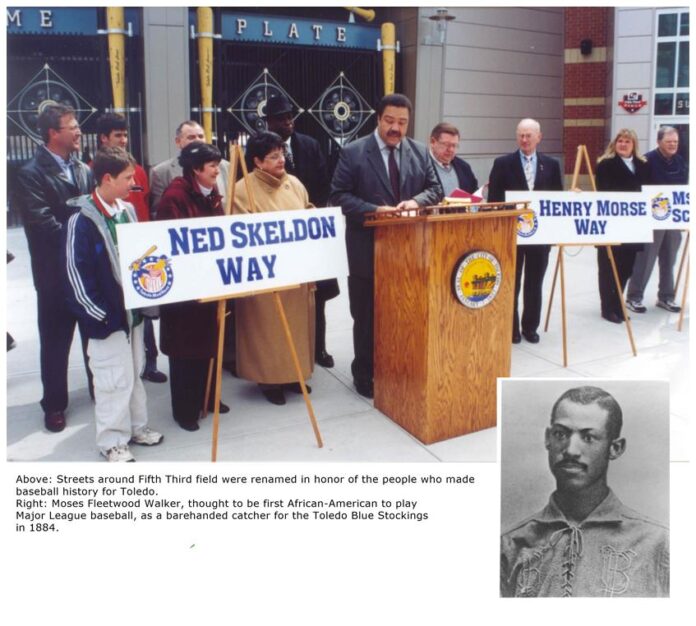

These six names are among those that appear on street signs and markers in the vicinity of the downtown ballpark. Their stories and many more make up baseball’s long and storied past in Toledo, which the Mud Hens are planning to honor with a weekend-long celebration of the city’s baseball history Aug. 3-5.

Gene Cook (1932-2002)

Gene Cook — who was the Mud Hens general manager before current president and general manager Joe Napoli — was a master innovator whose most lasting and legendary contribution to Toledo baseball may have been convincing actor and Toledo native Jamie Farr to wear a Mud Hens cap on the TV show “M*A*S*H,” according to Cook’s baseball-reference.com biography.

“USA Today Baseball Weekly called it ‘one of the great public relations moves in the history of minor league baseball,’” according to the site.

When Cook took the reins as general manager in 1978, baseball had been back in Toledo for more than a decade, but was floundering, said Mud Hens historian John Husman. Cook’s marketing efforts helped triple average attendance numbers.

“He really turned things around,” Husman said. “One of the first things he did was contact Jamie Farr and get him involved with the Mud Hens. You hear stories of Farr on ‘M*A*S*H’ — that was Cook doing that. Without a shadow of a doubt, we would have lost baseball in those years if not for him. He saved baseball for this city.”

Cook threw the last pitch at Ned Skeldon stadium and would have thrown the first pitch at Fifth Third Field, but died two months before the new ballpark opened, Husman said.

“He was a visionary about the downtown ballpark and one of the early proponents of it. You can’t say one man made it happen, but he probably did more than anyone to make it happen,” Husman said.

Cook, a longtime city councilman, vice mayor and member of the International League board of directors, came to Toledo after serving in the Korean War to attend the University of Toledo, where he played baseball, basketball and football and later semipro football.

“He was a great guy; I knew him,” Husman said. “He was a big man, a very intimidating-looking guy, but you never met a friendlier guy or a guy with a bigger heart.”

A baseball-shaped marker featuring the number “1” on it is installed at the far left end of the upper level facade at Fifth Third Field in honor of Cook. Washington street where it borders Fifth Third Field is Gene Cook Way. The Gene Cook Youth Athletic Foundation gives area children the opportunity to participate in athletics, including the Mud Hens’ annual Gene Cook Foundation Baseball Camp for Kids.

Casey Stengel (1890-1975)

The 2012 season marks the 85th anniversary of the 1927 Mud Hens team that won Toledo’s first league title.

The team was managed by Casey Stengel, who would go on to become one of the most famous managers in Major League history, leading the New York Yankees to seven World Series titles, including five consecutive titles.

Many people know his name, but most don’t realize Stengel spent his early career in Toledo, Husman said.

“His name is the most recognizable of any Mud Hen we’ve ever had. He was pretty successful here — although he also had a 200-loss season, so he did it all in Toledo,” Husman said.

After a professional playing career as an outfielder from 1912-25, Stengel managed and occasionally played for the Mud Hens for six seasons, from 1926-31.

“He was a character. He had a lot of witticisms called Stengelese. He talked in riddles, much the same as [another famous Yankees manager] Yogi Berra,” Husman said.

“I often wondered what it would have been like to be a pitcher with Stengel and then have Yogi come out. He wouldn’t know what the heck was going on.”

Stengel came to Toledo from a minor league team in Worcester, Mass., where he not only played but served as manager and general manager, Husman said.

“One of the stories he liked to tell is how he got here,” Husman said. “To make himself available to Toledo, he let himself go as a player, fired himself as manager and then resigned.”

Stengel was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966. In 1970, he became the first manager to have his number retired by two major league teams (Yankees and New York Mets); the second was Sparky Anderson (Detroit Tigers and Cincinnati reds) in 2011.

Ned Skeldon (1924-1988)

Edward “Ned” Skeldon is perhaps most widely known as the namesake for Ned Skeldon Stadium, the Maumee ballpark that was home to the Mud Hens from 1965 to 2001.

Today, North Huron street where it runs along Fifth Third Field is Ned Skeldon Way.

The Toledo politician and businessman was the driving force behind bringing baseball back to Toledo in 1965, Husman said.

“He probably did more than anyone else to get a team back in Toledo,” Husman said.

Skeldon’s daughter, Lucas County Commissioner Tina Skeldon Wozniak, recalls her father’s passion for baseball fondly.

“We tried to never miss a game. Even on the cold and rainy spring nights or the hot and balmy summer nights, we tried to be faithful fans of the Hens!” Skeldon Wozniak wrote in an email to Toledo Free Press.

“If my father were alive, he would have been a big advocate of building the stadium Downtown.”

“My family was very supportive of giving the team a new home in a state-of-the-art facility and at a perfect regional location, allowing Northwestern Ohioans an opportunity to enjoy America’s greatest pastime. I can’t thank the community enough for continuing to recognize him for his contribution to baseball in Lucas County. I smile every time I see the [street] sign.”

A graduate of Central Catholic High school and the University of Toledo and a World War II veteran, Skeldon served as a city councilman, county commissioner and vice mayor and on various boards.

After an unsuccessful run for mayor in 1965, he became the head of an organization devoted to cleaning up the polluted Maumee River. His dedication to the project led to a variety of publicity stunts attempting to demonstrate the waterway’s cleanliness, including gulping down a glass of river water in 1972 and swimming across the river in 1973, according to newspaper reports.

In an article published at the time of his death, friends recalled Skeldon as an energetic, enthusiastic visionary for Toledo.

“Ned was a real institution around Toledo and was the first person you called on with a problem,” said the late Harry Kessler, Toledo Municipal Court clerk, former mayor and longtime friend of Skeldon’s. “He told me that if something is good for a community, he didn’t want to hear 10 reasons why it should not be done, but one good reason why it should be done.”

Henry Morse (1908-1982)

Henry Morse, a graduate of Scott High school and the University of Toledo, was a respected Toledo banker and civic activist.

An executive with Toledo Trust, Morse was part of the committee of local civil and business leaders assembled by Ned Skeldon that brought baseball back to Toledo in 1965. Morse then served as the team’s first president.

According to a biography printed in a 1983 Mud Hens program, Morse was quiet and soft-spoken, often seen sitting behind the home plate screen with his trademark unlit cigar.

“There is no way to measure the number of individuals whose lives he touched as he counseled leaders in industry, business, education, religion, politics, social organizations and community agencies during 50 years of dedication to his fellow human beings,” the Medical College of Ohio trustees wrote in a resolution upon Morse’s death.

Monroe street bordering Fifth Third Field is named Henry Morse Way.

A number of other local sites also bear his name, including UT’s Henry l. Morse Physical Health Research Center.

Jerome Schmit (1910-1997)

Monsignor Jerome Schmit was a Catholic priest at The Historic Church of St. Patrick in downtown Toledo and also part of the committee assembled by Ned Skeldon to bring baseball back to Toledo.

“He was actually the guy who looked out at the old county fairgrounds (at the present location on Key street in Maumee) and said we ought to put some ball fields there,” said Skeldon, according to a 1981 newspaper article.

A graduate of st. John’s Jesuit High school, Schmit was a member of the board of directors for the Mud Hens and Lucas County Recreation Center and an advocate for youth sports.

“He used to go to all the Mud Hens games, but lately he hasn’t been able to because of his other duties,” Morse said in the article. “sometimes you can see him sitting in his car beyond the foul line outside the left-field fence saying his prayers and watching a few innings.”

Schmit, who overcame a speech impediment that nearly prevented him from entering the priesthood, was unrivaled at fundraising, sometimes employing unconventional methods to secure the funds he needed to keep his programs running.

Although he felt placing bets himself would be improper, Skeldon said Schmit would sometimes ask him to bet on a particular horse at the racetrack for him.

“He has a way of getting you to do things for him. You just want to do things for him,” Morse said in the article.

In a letter published in a 1998 Mud Hens program after Schmit’s death, church employee Martha Smith called Schmit “a gem” and “a great man.”

“He had the charm to raise money for charity drives, but he would never buy for himself, not even necessities,” Smith wrote. “He lived as if his money was destined for others. He opened his heart and his pocketbook to everyone. He never refused anybody. even if he was busy, he was always there for me or anybody else.”

North st. Clair street where it borders Fifth Third Field is named Msgr. Jerome Schmit Way.

Moses Walker (1856-1924)

Ohio-born Moses Fleetwood Walker is widely credited as the first African-American to play Major League baseball, as a barehanded catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1884.

He also played for Oberlin College and the University of Michigan.

Walker was known for his powerful throwing arm and aggressive base-running, according to a historical marker near the home plate gate of Fifth Third Field. The area is known as Moses Fleetwood Walker square.

Walker endured racial prejudice from teammates, opponents and fans.

He eventually left baseball to become a writer, inventor, civil rights advocate and entrepreneur. He was inducted into the Ohio Baseball Hall of Fame in 1991.