Colorful menace threatens agriculture, ecosystems

Story and photos by Christy Frank

TOLEDO – Swarms of spotted lanternflies recently hitchhiked their way into Downtown Toledo, and while they look pretty, their vibrant colors are a deceptive cloak for the havoc this invasive insect could unleash on area agriculture and ecosystems.

The spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) is an invasive agricultural pest that spreads by getting a ride on human transportation modes, such as trains and cars. Amy Stone, Agriculture and Natural Resources educator with The Ohio State University, said that’s why so many of them are in the downtown area.

“They are awesome hitchhikers, so we see them following rail lines or where people travel to and from,” explained Stone. She said populations are highest in areas with close proximity to train tracks, including East and South Toledo.

Originating from Asia, they were first discovered in the U.S. in Pennsylvania 10 years ago, and their infestation in Ohio now covers 12 counties. They are mostly only a nuisance for people, as they cannot bite or sting humans, but according to Stone, “ultimately, if we eat or drink, that is going to affect us, as well.”

Grapes, hops, hardwoods and fruit trees are among the affected plants. The lanternfly uses its needle-like mouth parts to pierce plant tissues and feed on the sap. This leaves plants weaker and more susceptible to diseases and can affect both the quantity and quality of crop productivity. Wine, beer, maple syrup and local fruits are all at risk.

This concerns Lisa Brohl, trustee with the Put-in-Bay Township Park District, who also grows grapes on South Bass Island for the Heineman Winery. “We’ve had drought conditions this year, too. We’ve got deer. This could be really bad.”

They have traps set up to monitor for the insect’s potential arrival and haven’t seen any on South Bass, but they’ve appeared in Castalia and Catawba, which is too close for comfort. A hitchhiking lanternfly on one visitor’s car could spell trouble for the island.

Brohl also serves as chair of the Lake Erie Islands Conservancy and is just as worried about trees in their forest.

“We had emerald ash borer so we have a lot of holes in our forest right now where the ash were,” said Brohl.

The insects eat maple and black walnut and she explained that “we can’t really afford to lose other components of our forest type here. I’d just hate to see that happen.”

She said they have been trying to be proactive there after first hearing about the lanternfly by treating the invasive tree of heaven, the preferred host plant for the insects. Brohl summed up her concerns about the unknown, comparing this experience with the area’s past lesson on zebra mussels and emerald ash borers.

“Anytime you get a hole in the ecosystem, you know, once you see that void, invasives are usually more poised to take advantage of disturbance than some of our native trees,” she said.

There are still a lot of unknowns about the insect and its potential impact. “We’re at the 10-year anniversary and we’ve learned a lot, but sometimes research takes time,” said Stone.

She said some early populations have decreased, but there is a chance they could rebound. Right now, Pittsburgh is a hot spot, with lanternfly swarms even showing up on radar, similar to the way Ohio’s mayfly season does on the thickest days. A few lanternflies on a plant aren’t likely to do significant damage, but they can be detrimental when there are tens or hundreds of them.

One study out of Pennsylvania State University found that lanternfly feeding reduced the sugar concentration in silver maples by 65 percent. This could lead to a decrease in maple production. More research needs to be done in this area.

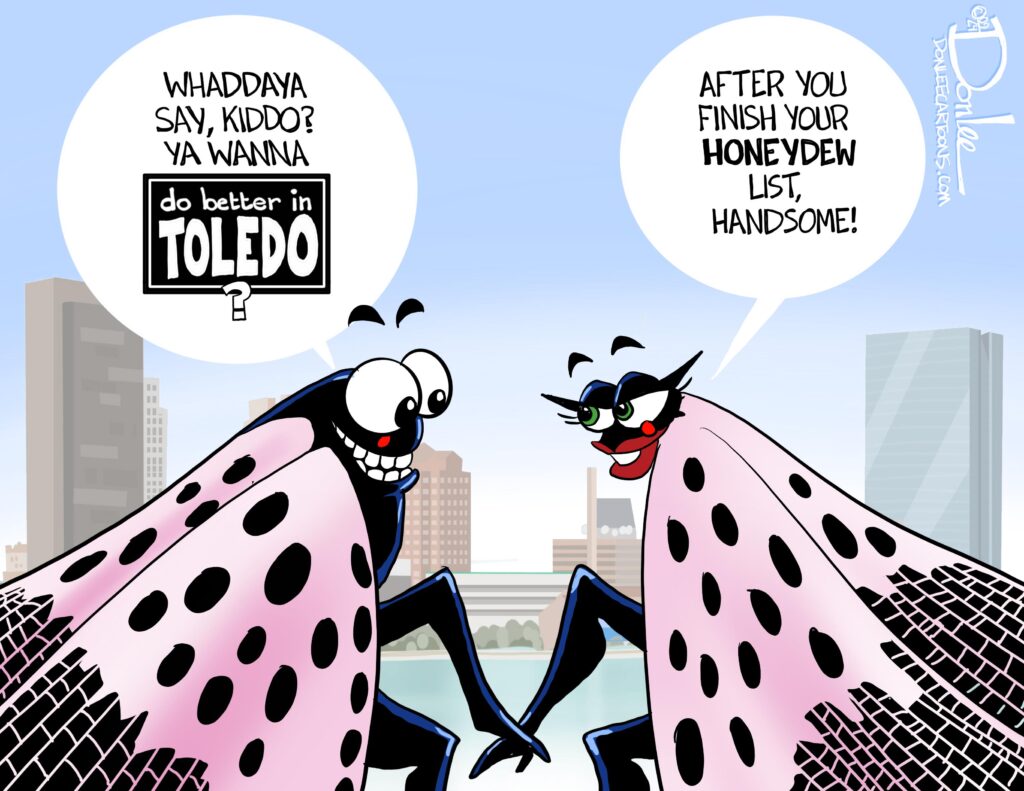

Another undetermined aspect of the lanternflies is the sweet and sticky substance they emit from their body after feeding. This excrement, called honeydew, leaves behind a residue in areas with a high population. Besides being a nuisance for people, there may be broader implications. Stone said honeybees are collecting this honeydew and taking it to the hive.

“Beekeepers are noticing in high populations that it changes the taste of their honey,” Stone said. Researchers continue investigating whether that alternative bee food source is beneficial or harmful.

They will most likely stick around until the first hard frost or freeze. Current swarms are probably due to mating, and Stone said egg masses are what they are on the lookout for next. “They’ll lay eggs that will winter over, and then that will be our population for 2025. So, once those eggs are laid, people could scrape the eggs to try to reduce populations.”

Stone says Lucas County residents don’t need to keep reporting findings on the Ohio Department of Agriculture website this year for locations where they’ve already filed a report or where there is a well-known infestation. However, knowing about the expansion is helpful if they travel somewhere new where it hasn’t been reported yet.

For more information about reporting and the spotted lanternfly, people can visit lucas.osu.edu.