For more than a century, the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA) has served as one of the most prominent jewels in the Glass City’s artistic crown. Wandering its galleries, visitors are treated to a representative sampling of the works of some of the greatest names their mediums had ever known. Rubens. Rembrandt. El Greco. Miyamoto. Kojima. Levine.

If those last few names seem out of place, perhaps the newest exhibition at TMA will help to change your mind. Beginning June 19, the museum’s Canaday Gallery became home to a show that spotlights the creative output of a canvas which has heretofore been left unchronicled within many galleries: Interactive media. Playable narratives. “The Art of Video Games.”

“The key to what the exhibition is about is in the title,” TMA Director Brian Kennedy said during a news conference with reporters on June 17. “It’s about, in a sense, in question, to what extent do you believe that video games are art, and what is the art form in video games?”

Smithsonian debut

“The Art of Video Games” exhibit is in many ways the brainchild of Chris Melissinos, former chief evangelist and chief gaming officer for Sun Microsystems. Working with the Smithsonian Institution, Melissinos crafted the show to demonstrate the evolution of gaming over a 40-year period, emphasizing how games grew, not just graphically, but artistically.

“A whole new culture has been established,” Kennedy said in an interview with Toledo Free Press. “Gaming is a usage of technologies to do something that we’ve never been able to do in this way before. And then, out of that, come certain artists that become very, very well known. And yet most of them, I don’t think, have yet emerged. This is such a new format.”

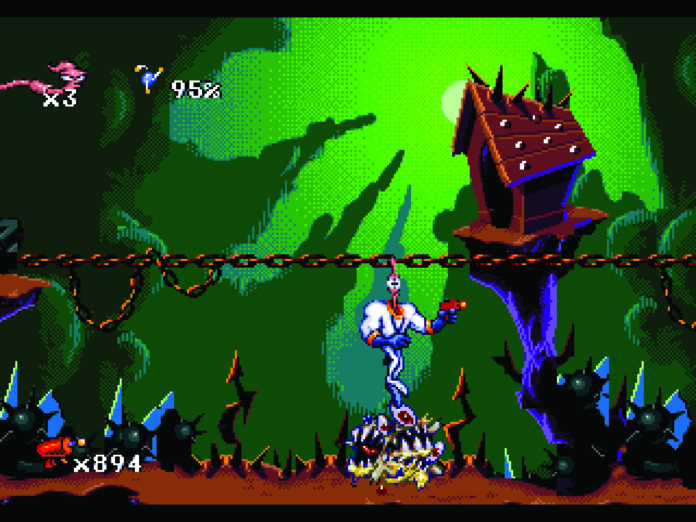

The exhibit was designed to tell the story of game development by dividing it into individual eras, with kiosks representing 20 different platforms. Art and videos showing examples of games that defined their time period are on display at each station. These representatives were voted on by the public, with players around the world choosing which titles best exemplified each era.

Five games are made available to be played by visitors: the original “Pac-Man,” “Super Mario Bros.,” the adventure game “The Secret of Monkey Island,” the groundbreaking point-and-click title “Myst” and the offbeat and beautiful PlayStation 3 title “Flower.”

“The Art of Video Games” was wildly popular during its initial run at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. “This exhibition was one of the most successful exhibitions in Washington at the Smithsonian — actually, the most successful exhibition they’ve had,” Kennedy said.

“And it just attracted people because there hadn’t been an exhibition on the art of video games.”

Back in time

Stepping into the exhibit, as it now stands in the Toledo Museum of Art, is less like walking into a gallery and more like traveling back in time to an arcade. The first sight is a 10-foot-high projection screen, showing Pac-Man wandering his trademark maze. The sounds of Mario collecting coins and stomping on enemies dominate the space as you wander the gallery. The entire experience is like being inside echoes of gaming’s past.

The look and feel of the show is quite deliberate, explained Amy Gilman, the museum’s associate director and point curator for “The Art of Video Games.” “I just have to give a little shout-out to our exhibition’s designer, Claude Fixler, who is the one who really works with each curator on the different shows, to come up with different ways of displaying for that show. And we do, we spend a lot of time thinking, ‘What is the best way for this show to be seen here in Toledo?’

“And with this exhibition, we had seen it in other venues, and the place that we saw it last was in a much larger space, it was more spread out. And we thought that, actually, for us to really make it more of a tight show, [we kept it] enough like an arcade that you immediately go there in your mind. We wanted it to be a little loud, we wanted it to feel a little visually crazy and all of that. And that’s a really important quality to video games, but it’s also an important quality to the experience of the exhibition.”

It’s a little jarring for someone familiar with the space — and with the museum in general — to see the transformation. Just a few months ago, the Canaday Gallery was home to a showing of works from the Tuileries Gardens of the Louvre. To see it as it is now might strike some as a vulgar offense to their delicate ideas of what “art” is.

But to Gilman, that contrast is crucial to the museum’s mission.

“For the museum, it’s really important that over time we have a really broad range of offerings for our visitors,” Gilman said to the gathered reporters. “And that means reaching out into communities that are not necessarily served by being our core audience, but it also means that we like to provide all our visitors with really different experiences.”

For anyone who lived through the console eras represented, the exhibit is certainly a genuine shot of nostalgia — a factor Gilman and her colleagues recognize.

“The fact that we chose to use Mario and Pac-Man as our graphics for this show is about the nostalgia for that period in video gaming that is very much alive today. So one of the things that’s very important to know is, this exhibition isn’t about showcasing the next latest game from Nintendo, or Wii or whatever, and being the launch for that. It’s actually about looking at the progression in a way that we who play video games in our basements probably don’t get a chance to do.”

It’s against the nature of the show — and indeed the medium it represents — to only dwell on the past, however. The four corners of the room are dominated by large projection screens where visitors can play one of the interactive titles, arranged chronologically. To see the progression of play — from “Mario,” where the goal is to stomp enemies and save the princess, to “Flower,” where you flutter on the breeze to invigorate a dying landscape — it’s hard not to see how narrative and genuinely artistic ideas have taken root for players the world over.

“With heightened, almost virtual reality, or hyperrealism in video capability now, we understand that it is more visually complex and that narratives are more complex, etc. But you don’t actually see how different it is in that progression, because we don’t actually look at it in that way,” Gilman said.

“So bringing them in here, and you being able to, start with the most pixelated, some of the most beloved, like Pac-Man. And you progress, and you can see them next to each other, you really get a sense of … not just the technical advances, but really, how visually and narratively complex things have become.”

“The Art of Video Games” is on display at the Toledo Museum of Art from now through Sept. 28. Admission is free.