Downtown Toledo developments: Partnerships with ConnecToledo

TOLEDO – Outside the Glass City Pavilion, the progress of the Glass City Metropark was on full display as Cheryl Hardy-Dillin spoke on improvements to Toledo’s downtown experience.

“We want downtown Toledo to be a place where you choose to come and enjoy yourself,” she said, highlighting the parks, sports events and musical happenings on the docket for this summer season.

“Events are not new to downtown,” Hardy-Dillin said, but admitted that the coordination between venues, businesses and other organizations has not always made the most of people’s time at the city center.

Hardy-Dillin, the community engagement specialist for ConnecToledo, spoke on economic development that could be easily accessed through creating reasons for people to come and stay — downtown.

“When you take the people that you bring to that entertainment venue, and then push them into the businesses and restaurants and buildings here intentionally…that then drives economic development.

For example, she said concerts in Promenade Park will begin at 6 p.m. and end at 9 p.m. which leads into other happenings. “We’re designing experiences that tie together.

“When the Metroparks has something going on over on this side of the river, we’ll be announcing what’s happening over here on our side of the river,” Hardy-Dillon said.

These planning initiatives were unveiled just as Toledo City Council approved $50,000 from the city’s general fund the day before for the 2025 Concert Series at Promenade park, under Oordinance 164-25.

The Promenade Park free concert series is a stimulus effort, in coordination with ConnecToledo, to get people downtown. City leaders and investors are hoping these kinds of events will lead to further revitalization of Toledo.

“Every concert, every gathering, every celebration, is intentional. It’s meant to draw people into the heart of the city and then push them into our local businesses,” Hardy-Dillin said, and then she pointed to the effect these kinds of coordinated programs could have.

“If we got a couple thousand people a week [downtown], and each person spent $35, we would reinvest a million and a half dollars [a year] into downtown Toledo.”

Matt Rubin, chairman of the Downtown Toledo Improvement District, said these kinds of reinvestments create civic pride for Toledo.

He noted that there’s been significant investment into downtown, over $2 billion over the last five years.

“We really need these events and activation efforts to bring people downtown so they can see and can be proud of their city,” he said.

Toledo Mayor Wade Kapszukiewicz weighed in with his own experience about being ‘nagged’ to bring back Party in the Park.

Truly, for eight years: ‘When are we going to bring Party in the Park back?’ It takes a little coordination and momentum to pull it off, but we’re finally doing that. It’s more than just nostalgia: It’s forward looking.”

Mayor Wade Kapszukiewicz

A number of new events are on the horizon, including Party in the Park, Lunch at Levis and Wellness at the Square schedules.

For a more expansive list of events happening in Toledo, checkout downtowntoledo.org

2025 Party in the Park Schedule

Free Concert Series & Family-Friendly Events

Where: Promenade Park | When: Friday Evenings

Opening Acts: 6–7 p.m., unless otherwise noted

Main Acts: 7:30 – 9:30 p.m., unless otherwise noted

Friday, May 30 | Zack Attack Band & Opener: Triplette’s

Friday, June 6 | Beef Carvers & Opener: The 25’s

Friday, June 13 | Hot Air Balloon Glow collaborative event at Promenade Park & Glass City Riverwalk Promenade Park: The Grape Smugglers (8-10 p.m.) & Opener: Mizer Vossen Project (6 p.m.);

Glass City Riverwalk: Hollywood Connection Band (7-10 p.m.)

Friday, June 20 | Distant Cousinz & Opener: Wall Music – Juneteenth Celebration presented by TARTA

Friday, June 27 | North of Nashville & Opener: J.T. Hayden

Friday, July 4 | City of Toledo Fireworks*

Friday, July 11 | Arctic Clam & Opener: Nikki D and the Sisters of Thunder

Friday, July 18 | The Day Drinkers & Opener: Funk Factory

Friday, July 25 | The Skittlebots & Opener: Daisy Chain – Christmas in July

Friday, Aug. 1 | Jeep Fest Activities*

Friday, Aug. 8 | Greggie and the Jets (Elton John Tribute) & Opener: Venyx

Friday, Aug. 15 | Toledo Pride Activities*

Friday, Aug. 22 | 90s R&B Jam – DJ Lyte N Rod, Wall Music & Friends, Hosted by Big Trice

Friday, Aug. 29 | The Ultimate Garth Brooks Tribute Band & Opener: Ashley Martin Band (8–10 p.m.); Drone Show at 10pm – “Thank You Toledo” Appreciation Night

*Note: Events marked with an asterisk are supported, but not directly programmed by ConnecToledo

20th Anniversary of Lunch at Levis

Grab takeout from a local restaurant or food truck and enjoy free live music and fun at this lunchtime event series!

When: June 5 to Oct. 2, 2025

Every Thursday afternoon from 11:30 a.m. – 1:30 p.m.

Where: Levis Square Park

2025 Food Truck Lineup

Baba’s Eats, Beastro Burger, Deets BBQ, Falafel King, Fat Boyz, Lyles Crepes, The Loaded Chicken, Wanna Make ‘Er Loaded, Trip ‘n Biscuits, Stubborn Brother, Naan Stop Kebap, Better Than Yo Mama’s, Casero Kitchen, PM Frosted Fantasies, BD’s Lemonade King, Bean Crazy 419 & Guac Shop

Thursday, June 5 – Kickoff Event | DJ Jon Zenz

Thursday, June 12 | Michael Corwin

Thursday, June 19 – Juneteenth Celebration | Distant Cousinz Trio

Thursday, June 26 | Chris Knopp

Thursday, July 3 – Independence Day Event | Shane Piasecki

Thursday, July 10 | New Moon

Thursday, July 17 | Ben DeLong

Thursday, July 24 – Christmas in July Event | Arctic Clam

Thursday, July 31 | Chloe & The Steel Strings

Thursday, Aug. 7 | Mud Hens Hype Bash

Thursday, Aug. 14 | Chavar Dontae

Thursday, Aug. 21 – Local Vendor Market | Tim Oehlers

Thursday, Aug. 28 | Water Street Band

Thursday, Sept. 4 – UT Football Hype Bash | DJ Super Nathan

Thursday, Sept. 11 | Terry & Charlie

Thursday, Sept. 18 | Ora Pettaway

Thursday, Sept. 25 | Tony Salazar

Thursday, Oct. 2 | DJ Jon Zenz

Wellness at the Square Schedule

Free yoga and fitness classes. All fitness levels welcome!

When: Saturday Mornings from 11 a.m. – noon

Where: Levis Square Park

Saturday, Aug. 9 | Yoga led by Toledo Mindfulness Institute

Saturday, Aug. 16 | Strength Training led by The Standard Fitness Academy

Saturday, Aug. 23 | Yoga led by Danielle Nolff

Saturday, Aug. 30 | Strength Training led by Gamefit HQ

Saturday, Sept. 6 | Mindful Fitness led by Toledo Mindfulness Institute

Saturday, Sept. 13 | Yoga led by Parting Clouds Yoga

Saturday, Sept. 20 | Strength Training led by The Standard Fitness Academy

Saturday, Sept. 27 | Yoga led by Parting Clouds Yoga

Announcement Briefs

(Announcements are compiled from press releases and in order received)

NEWS SHORTS BRIEFS ARE UPDATED DAILY

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Mom’s House, Pregnancy Center celebrate new Laurie’s Place

TOLEDO – Today, one year after breaking ground, Mom’s House and The Pregnancy Center celebrated the grand opening of Laurie’s Place, a collaborative new space designed to empower and support Toledo families. The milestone marked the culmination of a shared vision and a year of progress made possible by generous donors and unwavering community support.

Located at 722 N. Westwood Ave., Laurie’s Place will serve as a second location for Mom’s House and a new hub for The Pregnancy Center’s expanded services. Together, the organizations aim to remove barriers for single parents and families—providing access to free early childhood education, parenting resources, life skills training, and wraparound support. While this is a collaborative effort, Mom’s House and The Pregnancy Center remain two separate, independent organizations. Their partnership demonstrates the power of collaboration—each bringing their unique strengths to better serve the community.

Laurie’s Place was named in honor of Laurie Moore, whose legacy of love and caregiving inspired the project. Her husband, Bob Moore, provided an anchor gift to the organizations’ “Rattle the Stars” capital campaign, setting the foundation for what would become a $12.1 million community endeavor. Thanks to the generosity of 390 donors, the campaign reached its goal and brought the vision to life.

A central feature of the new facility is the TO-GET-HER space—a revolutionary concept that allows community partners to deliver services under one roof. This model streamlines access to care and resources for families, creating a more holistic and accessible support system.

To learn more about Laurie’s Place and the continued efforts of the “Rattle the Stars” campaign, visit rattlethestarstoledo.org. (05/14)

BGSU professor selected as 48th Probst Memorial Lecturer

BOWLING GREEN – A Bowling Green State University researcher recently joined a notable list of Nobel laureates after being selected as the guest speaker for the 48th William J. Probst Memorial Lecture, recognizing their expertise and advancements in the field of photochemistry.

Dr. Jayaraman Sivaguru, a distinguished university professor in the Department of Chemistry and world-renowned BGSU Center for Photochemical Sciences, has dedicated his career to advancing research in photochemical sciences, working with Fortune 500 companies and collaborating with industries to solve real-world problems.

As part of this year’s lecture at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, Sivaguru presented “Lessons from Light for Life and Leisure” and “Harnessing the Power of Light to Drive Chemical Changes.”

Sivaguru’s impact on the science field goes beyond his classroom each year when he engages with local school districts through the PICNICS program at BGSU.

Open to high school students, Sivaguru and BGSU students offer a six-week science-based experience that empowers high school students to engage in real-world, cutting-edge research in BGSU science labs. Students conduct daily laboratory activities before presenting their findings at a public event.

Sivaguru is slated to present at the prestigious Gordon Conference later this year and will also co-organize the Pacifichem Symposium on “Photosciences in Molecular and Supramolecular Scaffolds” hosted by the International Chemical Congress of Pacific Basin Societies. (05/14)

Place your bet on Imagination Station‘s All In for Science

No beginner’s luck needed! It’s time to go All In for Science at Imagination Station’s Celebrity Wait fundraiser on Tuesday, June 10 at 6 p.m.

Enjoy a four-course meal at the Hollywood Casino’s renowned Regalo restaurant, served by our local celebrity waiters—community leaders and changemakers who believe in the power of STEAM.

What: Imagination Station’s Celebrity Wait fundraiser

When: Tuesday, June 10 | 6 p.m.

Where: The Hollywood Casino | Regalo

Throughout the night, you’ll be treated to an evening of specials prepared by Regalo’s culinary team. However, the real jackpot of the night is the support raised for Imagination Station. Proceeds from the night go right back to the science center, strengthening and expanding programming and community outreach, helping Imagination Station fuel the dreams of future scientists and innovators.

Get ready to have a winning night for STEAM and go ALL IN for a brighter future.

To purchase tickets for Celebrity Wait or make a donation to the science center, visit imaginationstationtoledo.org. (05/14)

Gavarone recognizes Wood County Public Library’s anniversary

COLUMBUS — State Senator Theresa Gavarone (R-Bowling Green) recognized the Wood County District Public Library for reaching the significant milestone of a 150th anniversary.

“Times have changed but this library has changed with the times,” said Gavarone. “This facility is still an invaluable resource for our community, and we anticipate it will be a beneficial and loved neighbor for at least another century and more.”

The library has become much more than simply a place to borrow a book. It now offers “150 Things To Do,” which include using a 3D printer, getting help earning a GED, and renting movies for free. Click here for a full list of activities the library offers.

The Wood County District Public Library is the earliest known public library in Bowling Green, established in 1875. The library initially moved around to different locations, largely dependent upon who was serving as librarian at the time. (05/11)

Kristaun Self sentenced for fatal shooting, arson

TOLEDO – Lucas County prosecuting attorney Julia R. Bates announced that on May 9, a Lucas County Common Pleas Court judge sentenced Kristaun Self to 25 years in prison.

In State of Ohio v. Kristaun Self, the defendant pleaded guilty to five charges: involuntary manslaughter, aggravated robbery with a gun specification, aggravated arson, tampering with evidence and the abuse of a corpse.

On Nov. 8, 2023, Self met Josiah Gill on Esther St. in Toledo to trade handguns. Self then shot Gill and set his body on fire in the back seat of Gill’s car beneath the Veterans’ Glass City Skyway. Because Self was a juvenile at the time of the offense, he would have been eligible for parole after 25 years under Ohio law.

This was a brutal and deliberate crime,” Lucas County Prosecuting Attorney Julia R. Bates said. “The defendant chose violence, destruction and concealment over basic human decency. I hope Josiah Gill’s family can find a degree of peace and that his memory lives in their hearts.”

Assistant Lucas County prosecutors Joe Gerber and David J. Borell led the prosecution. (05/11)

Maumee Valley hires David Skoczyn as soccer coach

TOLEDO — Maumee Valley Country Day School today announced the hiring of David Skoczyn as the new head coach of the boys’ varsity soccer team. With nearly three decades of coaching experience and a proven record of success across multiple programs in Northwest Ohio, Skoczyn brings leadership, a strong developmental philosophy, and a history of competitive excellence to Maumee Valley’s soccer program.

Skoczyn most recently served as head varsity coach of the boys’ team at Evergreen High School, where he compiled an impressive 54-18-4 record from 2020 to 2024. Under his

leadership, Evergreen captured league, sectional, and district titles and reached the

regional semifinal. His commitment to program-building was evident in his development

of a junior varsity squad and implementation of year-round fitness and technical training

programs.

Prior to his tenure at Evergreen, Skoczyn served as associate head coach at Notre Dame

Academy, amassing a 102-23-10 record and guiding the team to League, Sectional,

District, and Regional championships as well as an appearance in the State Semifinal. He

has also led varsity programs at Cardinal Stritch, Celina High School, and contributed

significantly to youth development through coaching roles at Pacesetter Soccer Club and

as director of coaching at Grand Lake Soccer Club. (05/11)

Surprise teacher award announcement for Start HS teacher

Start High School teacher Tim Pettaway will be recognized by the Total Purpose Scholarship Foundation as a 2025 Changemaker in Education Distinguished Teacher of the Year honoree. The foundation is coordinating a surprise in-person announcement to recognize Mr. Pettaway for his work and commitment to the Toledo community on Monday., May 12. (05/11)

Yemisi Shyllon Museum of Art and TMA launch historic cultural exchange to boost museum expertise, global access

In a landmark move that sets a new precedent for international cultural collaboration, the Yemisi Shyllon Museum of Art (YSMA) in Nigeria and the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA) in

the U.S. announce a transformative partnership aimed at promoting modern and contemporary African Art and enhancing institutional capacity through knowledge exchange.

Formalized through a memorandum of understanding signed in November 2024, the partnership will see both museums – nonprofit, educational institutions with a shared mission of service and impact through art – collaborate on a range of programs including a training and professional development exchange, joint curatorial initiatives, and traveling exhibitions from YSMA’s collection to the U.S.

This collaboration marks YSMA’s first major international partnership and is a bold step in amplifying its reach and influence on the global stage, particularly in deepening U.S.–Nigeria cultural relations through the lens of art and heritage. Recently named the 2025 Best Art Museum in the USA TODAY 10Best Readers’ Choice Awards, TMA is an institution renowned for its history and reputation in museum management, curatorial excellence, and

public engagement.

Highlighting the significance of the collaboration, Adam Levine, director and CEO of TMA said, “At the Toledo Museum of Art, we are proud to engage in a partnership that fosters mutual learning, inclusivity, and global dialogue. This collaboration with YSMA not only enriches our understanding of African art traditions but also deepens our ability to integrate art into the lives of people — both locally and globally. By working together, we strengthen the institutional ties and cultural connections that inspire, educate, and promote access to the transformative power of art.” (05/08)

Scott Kepp promoted to president at GEM Inc.

WALBRIDGE – Scott Kepp has been named president of GEM Inc., one of The Rudolph

Libbe Group of companies, which focuses on specialty trades construction, manufacturing

and industrial process, facility maintenance and ongoing management.

Kepp replaces Steve Johnson, who retired in late April after 37 years with the company,

including 10 as President.

“I’m excited to continue the growth and progress that GEM made under Steve,” Kepp said.

“Our focus will be on safety, maintaining high quality standards, winning new customers by

demonstrating the value we can bring to their projects, and keeping our commitments to our current customers.”

Kepp, of Perrysburg, Ohio, joined GEM in June 1997 as an assistant project manager, and

progressed to his most recent position of Senior Vice President. He holds a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from Carnegie Mellon University. Kepp is active in the industry and in the community, currently serving on the board of the Mechanical Contractors Association of Northwest Ohio as immediate past president, and as a member of the Rotary Club of Toledo.

Based in Toledo, Ohio, since 1982, GEM Inc. is a specialized resource for customer facility and process construction needs. GEM offers design, renovation, upgrade, consolidation and

relocation services for process manufacturing and industrial customers and directly employs its team of skilled construction craftspeople. Markets served include automotive, chemical, food processing, healthcare, metals, power and refining. (05/08)

Commissioner Sobecki testifies on state’s operating budget provisions before Ohio Senate Government Oversight Committee

COLUMBUS – Lisa A. Sobecki, president of the Board of Lucas County Commissioners, testified on Wednesday, May 7, to the Ohio Senate Government Oversight Committee to highlight provisions she believes must be included or preserved in the state’s operating budget in order to strengthen Lucas County’s infrastructure, improve public safety and support the health of our residents.

During her testimony, Sobecki thanked the Ohio House for including language that requires the Department of Medicaid to pursue an 1115 waiver for Medicaid coverage of pretrial detainees in county jails and strongly encouraged the State Senate to do the same.

Sobecki also urged the committee to include $20 million in funding for a dedicated H2Ohio Ash Tree Removal Grant Program. The emerald ash borer infestation has left thousands of dead trees in and near rivers, creeks, and drainage channels in communities across Ohio, including Lucas County.

Additionally, Commissioner Sobecki asked the committee to return the governor’s plan for jail construction grants, which would support Lucas County’s long-planned new pretrial detention center in downtown Toledo.

She also highlighted the need for strong cybersecurity investments in counties across Ohio and advocated for an increase of the Local Government Cybersecurity Grant to $15 million in each fiscal year.

Finally, she urged the Ohio Senate to maintain the Local Government Fund proposed by Governor Mike DeWine and upheld by the Ohio House. (05/08)

You can watch Sobecki’s full testimony on the Ohio Channel online here.

Happenings Calendar

(Happenings are compiled from press releases and placed in order of occurring dates)

NEWS SHORTS BRIEFS ARE UPDATED DAILY

HAPPENINGS

UToledo footbridge installation set for Thursday

TOLEDO – The University of Toledo’s new pedestrian bridge over Douglas Road is now scheduled to be set into place Thursday, May 15.

Contractors are expected to begin connecting the two prefabricated sections that will make up the 78-foot span around 8 a.m. A crane is expected to begin lifting the bridge into place around 10 a.m.

Douglas Road will be closed between University Hills Boulevard and East Rocket Drive from approximately 5 a.m. to 8 p.m. while work is being completed. A detour will be posted.

The footbridge, which will be near the northeast corner of Savage Arena on the western side of Douglas Road and the intersection of Marwood and North Westwood avenues on the eastern side of the road, will more directly connect the university’s engineering buildings to the rest of main campus, improving safety for pedestrians going between the two areas of campus.

UToledo broke ground on the $3.4 million bridge project in July. Construction crews have been working since then on the bridge foundations as well as the stairs and ramps that will provide access to the elevated walkway.

Food for Thought holds 10th annual Jam City fundraiser

TOLEDO – Food for Thought is continuing a Toledo tradition again this year. Join the party to benefit the important work Food for Thought does in the community.

This event brings together 15-20 of the best local restaurants Toledo has to offer, each one

creating and serving their own gourmet take on the lunchtime classic: Peanut Butter & Jelly. There will be signature cocktails, a silent auction, 50/50 raffle, photo booth, and live music featured throughout the evening.

Jam City has been a sell-out event almost every year in the past. This year will be no

different as the event is expected to bring in more than 200 people to come together for an evening of food and fun!

May 15 from 6-8 p.m. in the Fifth Third building lobby at One Seagate, Downtown Toledo

Museum to show The Ghost, Mr. Chicken at Classic Movie Night

FINDLAY – The Hancock Historical Museum’s popular Classic Movie Night series continues

this month with the spooky-comedy favorite The Ghost and Mr. Chicken (1966), screening on Friday, May 16 at 7 p.m.

Starring Don Knotts and Joan Staley, this lighthearted mystery follows timid typesetter Luther Heggs as he braves a night in a haunted mansion to prove himself as a reporter. Filled with quirky charm, ghostly hijinks, and small-town suspense, this cult classic remains a beloved showcase of Knotts’ comedic genius.

This screening will be hosted by Haley Shipley, a 4th year American Cultural Studies Ph.D.

student and a student supervisor at the Browne Popular Culture Library. Haley is a member of the Ray Browne Association (RBA), a student organization at Bowling Green State University dedicated to the study and appreciation of popular culture. As part of a new 2025 initiative, RBA students will provide historical background and facilitate discussion at select movie nights throughout the year.

Classic Movie Night is free and open to the public. Doors open at 6:30 p.m., and seating is

limited. The film begins at 7 p.m. Complimentary popcorn and refreshments will be available.

The screening will be held at the Hancock Historical Museum, 422 W. Sandusky St.

TLC luncheon to feature Boys & Girls Clubs of Toledo alumni

TOLEDO – Boys & Girls Clubs of Toledo alumni will take center stage at the organization’s 16th annual TLC Luncheon presented by KeyBank and the Walter Terhune Foundation. The theme is “Clean. Safe. Fun.”

John Miller, retired senior vice president of affiliate relations for Boys & Girls Clubs of America, will moderate the discussion. He began his Club career in 1988 as a resident camp director for the Boys & Girls Clubs of Toledo.

Panelists are:

- Dr. Mieasha Hicks Barksdale is a double board-certified podiatric foot and ankle surgeon and the founder of Foot & Ankle Specialist of Indiana, based in central Indiana. In 2003, she was honored as the National Youth of the Year by the Boys & Girls Clubs of America.

- Keyaunte Jones is a second-year dental student at Meharry Medical College. He plans to specialize in oral surgery. In 2017, he was honored as the Boys & Girls Clubs of America’s Midwest Youth of the Year.

- Tobria Layson is a dedicated healthcare professional and community leader in Houston, Texas. She holds a degree in nursing from Lourdes University and is a licensed registered nurse. In 2010, she was Boys & Girls Clubs Ohio Youth of the Year and Boys & Girls Clubs of Toledo’s Carson Scholar.

Tickets for the event are $125 and available at bgctoledo.org/tlc. A social mixer begins at 11 a.m., with the program at noon.

All proceeds benefit Boys & Girls Clubs of Toledo. The organization’s nine locations across Toledo offer after-school and summer programming to about 4,000 youth aged 7 through high school graduation each year.

Friday, May 16 at noon at the Mosaic Ballroom at the Renaissance Hotel Downtown Toledo. Door opens at 11 a.m.

Opera Presents: Opera Cabaret

TOLEDO — Toledo Opera will present the second installation of Opera Cabaret on May 17. The event will feature performances by the Toledo Opera Resident Artists and members of the Toledo Opera Chorus.

Opera Cabaret will be hosted by Toledo Opera Artistic director Kevin Bylsma. Refreshments will be provided, and this event is free and open to the public. A freewill donation will be accepted on the evening of the event, and will be used to sustain and develop the Toledo Opera Chorus.

For Toledo Opera artistic director, Kevin Bylsma, the return of Opera Cabaret is both a celebration of local talent and a chance to connect more personally with the community.

Opera Cabaret is a new performance series developed by Toledo Opera to spotlight the artistry and talent of the Toledo Opera Chorus. The program was conceived following the company’s production of South Pacific, which featured a small and specialized ensemble. In response, the artistic staff created Opera Cabaret as a platform to fully showcase the chorus – a group regarded as the heart of Toledo Opera. Comprised of regional and local professional singers, the Toledo Opera Chorus plays an essential role in bringing each mainstage production to life.

These dedicated artists generously contribute their time, talent, and passion to the company. Opera Cabaret offers them the opportunity to shine in a more intimate setting, while also deepening connections with the community through varied vocal selections and engaging performances.

Saturday, May 17 at 7 p.m. at the Toledo Opera offices (425 Jefferson Avenue, Suite 601 in Toledo. For more information, visit toledoopera.org. For media access, please contact Rachael Cammarn at rcammarn@toledoopera.org.

Experience TARTA job fair held for TARTA job candidates

TOLEDO – The Toledo Area Regional Transit Authority (TARTA) continues to look for dedicated, career-minded individuals with a passion for connecting people to their communities.

At the Experience TARTA event, job seekers can complete applications, speak with

TARTA’s Human Resources team about open positions, and even drive a bus through

a secured course.

TARTA is currently hiring fixed line operators, a maintenance supervisor and utility

mechanics, but those interested in other jobs may still come to the event to speak

with HR personnel about the benefits of working for TARTA.

“It isn’t just about being able to give driving a bus a try; we want anyone who is

interested in helping our community by pursuing a career in transit to join us and get

a sense of what it’s like to be on Team TARTA,” Barrera-Richards said.

Applicants who want to drive the bus at this event:

Be at least 21 years old

Have a high school diploma or GED

Have a valid operator’s license with no more than two points in the last three years.

Saturday, May 17, 9 a.m. to noon at 1127 W. Central Avenue in Toledo –

Disabled Women Make History (and Art) returns to TMA

TOLEDO – The Toledo Museum of Art (TMA), in partnership with the Disability EmpowHer Network, is proud to present the fourth annual Disabled Women Make History (and Art) exhibition.

This vibrant event showcases the work of 20 selected artists with disabilities and provides an opportunity for the public to meet the artists, view their work, and celebrate the intersection of art, identity and advocacy.

More than 90 artists applied to participate this year, working across various mediums including painting, sculpture, fiber, and mixed media. A quick program will kick off the evening, followed by time for guests to mingle with artists and explore the exhibition. Light refreshments will be served. The event is free and open to the public.

“This event is about more than displaying beautiful and compelling artwork—it’s about community, representation, and providing a platform for voices that are too often unheard,” said Katie Shelley, TMA’s Conda Family Manager of Access Initiatives. “These artists are sharing not just their creativity, but also their lived experiences. That’s powerful.”

Disability EmpowHer Network director of programs Sophie Poost added, “When disabled women are given space to tell their stories through art, the impact is transformative—not only for the artists, but for every visitor who experiences the exhibition. This program empowers artists to lead, speak up, and make history through their work.”

As part of the program, artists will participate in workshops the day of the exhibition, including a session on pricing their artwork for sale and a public speaking workshop designed to build professional and personal confidence.

Disabled Women Make History (and Art) is made possible in part through the generosity of the Ohio Olmstead Task Force and the Ohio Statewide Independent Living Council.

Saturday, May 17, 6–8 p.m. in the TMA Glass Pavilion.

Imagination Station May events: Hockey, Wicked, art and music

> HOCKEY: Faster Than Ever | All Day | Free for Members, $5 for non-members | Buy Tickets

Don’t hang up your skates just yet, T-town! HOCKEY: Faster Than Ever is now extended through August 31. You can score a visit to the coolest exhibit all summer long and see a power play of science and sport.

> Wicked Sing-Along | May 17, 2:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. | Buy Tickets

Imagination Station is turning into Shiz University for one day only that will give you a chance to fly! Join us for two special sing-along showings of the most pop-u-lar movie out there.

> Colleen Welsch: May 16-18 | All Day

Step inside a real music production studio at Imagination Station with music producer, singer-songwriter Colleen Welsch. Visitors will explore the technology and science behind sound recording as they make their very own song.

Toledo Opera to Hold Children’s Chorus Auditions for Carmen

TOLEDO – Toledo Opera is seeking boys and girls ages 9-14 with unchanged voices to sing in the children’s chorus of Carmen (August – October 2024 commitment).

Bizet’s sizzling epic of dark passion, Carmen, tells the story of a fierce woman who lives life on her own terms – and the men who can’t let her go. Don José, a soldier drawn into her orbit, abandons everything for Carmen’s love, only to find himself consumed by jealousy when her attentions shift to the dashing bullfighter, Escamillo.

With its twisting tale of romance, deceit, and disaster set to magnetic melodies, Bizet’s masterpiece, Carmen, has become one of the world’s most celebrated operas. Featuring some of the most popular music to ever grace the opera stage, Carmen brings every aspect of Bizet’s thrilling tale to life, from its tantalizing beginning to its devastating climax. Under the baton of Adam Turner (Toledo Opera’s Il Trovatore and Roméo & Juliet), Toledo Opera’s vibrant original production is not to be missed.

Rehearsals will take place on Sundays from 4 p.m. to 4:45 p.m. at the Toledo Opera Offices. To schedule an audition, please email James Norman at jnorman@toledopera.org.

Auditions: Saturday, May 17, 10 a.m., and on Sunday, May 18, 3 p.m. until 6 p.m.

> Auditions will be held at Toledo Opera Offices, 425 Jefferson Ave., Suite 601.

The Arts Commission to Launch New Project Grant in 2025

TOLEDO – The Arts Commission has announced a new Project Grant pilot program in 2025.

In a press release, The Arts Commission stated that it “deeply values the vibrant and diverse creative community that defines Toledo. We recognize the important role artists play in shaping the city’s identity and are dedicated to supporting their growth and sustainability.”

Through its granting programs, The Arts Commission offers direct support to artists at different stages of their careers, helping them pursue new projects, develop their creative practice, and contribute to the region’s cultural landscape.

The Project Grant is a competitive program offering financial support to artists of all mediums to create or complete original works of art that show artistic growth and creative experimentation. Emerging, mid-career, and established artists are encouraged to apply.

Eligible categories of support related to the creation and completion of a creative project include materials and supplies, equipment, and project support. Artists may request funding at the $2,000, $2,500, or $3,000 level. Requested grant amounts should not exceed $3,000.

Individual artists and members of artist collectives with a current residence or creative studio within 30 miles of downtown Toledo may be eligible.

Grant guidelines and the application link can be found on The Arts Commission’s website theartscommission.org.

Applications open Monday, May 19, and must be submitted before the deadline of 11:59 p.m. on Sunday, June 8.

Miller Ferries honor American veterans on Memorial Day weekend

Put-in-Bay – Miller Ferries will offer active U.S. military personnel and American veterans free passenger fare in honor of Memorial Day. Military personnel and veterans are asked to please present military identification at the Miller Ferry ticket booths in order to receive a free round trip passenger ticket to Put-in-Bay or Middle Bass Island.

On May 26, the National Park Service’s Perry’s Victory and International Peace Memorial on Put-in-Bay will have a Memorial Day Ceremony. It will pay tribute to everyone who has defended the United States of America – from the Revolutionary War to the Afghanistan War.

Saturday, May 24 through Monday, May 26.

> For ferry schedules, visit MillerFerry.com.

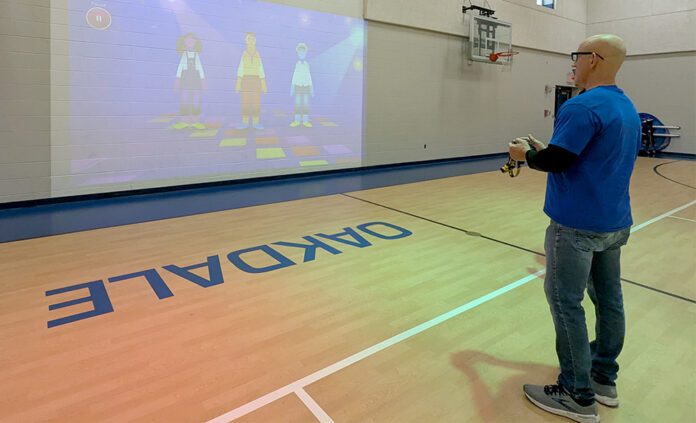

TPS rallies to combat absenteeism

Oakdale Elementary participates in “making every day count”

TOLEDO – Public school attendance has dropped nationally since the COVID-19 pandemic and, for most schools, has never returned to pre-COVID levels. Toledo Public Schools (TPS) decided it was time for that to change.

TPS started an attendance incentive program in elementary schools, called Let’s Make Every Day Count, which rewards students for consistently showing up to class.

These incentives range from tickets to professional basketball games and ice skating trips to prizes, like drones.

Let’s Make Every Day Count is provided by a grant partnership program that uses outside funds rather than district tax dollars.

“I’m not going to turn down an incentive program for any kid. And if the district wants to be a part of it and it helps us save funds, we’re going to be a part of that process here at school because we are always looking for funds here at East Toledo,” said Oakdale Elementary principal Robert Yenrick.

Yenrick said these programs have occurred for the last two years but have picked up significantly this past year.

Chronic absenteeism, characterized in Ohio as missing 15 or more days of school, has many negative outcomes for a child’s learning experience.

Rates of illiteracy and dropping out of school greatly increase for chronically absent students, the AP News reports. Oakdale’s 35 percent chronic absenteeism rate is caused by many factors.

“Homelessness is a big issue for some schools and families,” Yenrick said.

With homelessness and poverty often comes a lack of transportation. Oakdale has worked to fill this need with a behavior partners group called New Concepts, which helps impoverished students and/or students who lack transportation get to school. But without community support, programs like New Concepts cannot succeed.

“There are all kinds of needs people have. And we have needs as a school, too,” said Yenrick.

Community members can get involved by making meals for food-insecure families, participating in the New Concepts program, tutoring, moderating recess, or making meals for Teacher Appreciation Week.

Without community support, extra work and financial burden falls on Oakdale teachers.

“We had a Lego club with no Legos,” Yenrick said.

Lego purchasing was left to the Lego Club teacher’s own dime.

Yenrick encouraged community involvement, saying it could help support student education and well-being and alleviate some of the burden that falls on teachers.

While community involvement can be increased with a little encouragement, some factors of absenteeism, such as illness, are a little harder to control.

Yenrick said that for students who get multiple viruses during the academic year, those 15 absent days add up quickly. Despite the challenges, Oakdale works to make learning fun for students and encourages them to attend class.

One way Oakdale has done this is by implementing Lü Interactive Systems, a learning game system that projects onto the gym wall.

“It [Lü] is the first one in an urban school in the northern part of the state. All the others are [in] suburban schools,” Yenrick said.

Students can play games on Lü that have learning or exercise benefits, such as interactive math games and dance games that can be played during gym class.

Oakdale gym teacher Steve Thurn said he watches the kids come alive when they play the Lü dance game.

Thurn said tutors also use the game to help children struggling with particular school subjects, such as memorizing multiples of five. Lü’s interactive math games help students have fun while also improving their education.

Oakdale also encourages the balance of learning and fun by sending kids to camp through a YMCA program.

“We’re looking to get businesses to do sixth-grade camp,” Yenrick said. “I’m trying to raise money for the majority of the Eastside schools to go to camp through sixth grade. I want these kids to experience a portion of life that’s just different than what they see every day, and give them the chance to say ‘Hey, there’s a different world out here that I don’t know.’”

UToledo to cut multiple undergrad programs to comply with SB 1

This story was originally published on WTOL, a media partner of the Toledo Free Press.

By Troy Gingerich | WTOL

TOLEDO — The University of Toledo announced plans to suspend admission to several undergraduate degree programs to comply with recently passed Senate Bill 1 in Ohio, and cuts to other degree programs as part of a “prioritization process.”

UToledo plans to phase out several low-enrollment degree programs starting with the 2025-26 academic year. While admissions to these programs will be suspended, the university says students already enrolled in these programs will be able to finish their degrees without interruption.

The university says the prioritization process is in response to a “challenging time in higher education,” as colleges are dealing with a declining population of high school graduates entering college, current student retention challenges and rising costs of operation.

“This effort is aligned with the UToledo Reimagined strategic plan that includes the stated goal to deliver relevant and innovative academic programs,” the university’s website says.

“While there may be some immediate cost savings, the goals of this effort are more focused on growth as UToledo’s student enrollment, retention and graduation rates improve as the University becomes more competitive.”

UToledo says the Office of the Provost worked alongside college deans to evaluate programs based on several factors, such as student and workforce demand, accreditation requirements and the potential to offer courses as minors or certificates instead.

Courses in the affected areas will still be available as part of the university’s core curriculum or as components of minors and certificates, the university says.

The timing of these moves coincides with new state requirements. Ohio Senate Bill 1, recently signed into law by Gov. Mike DeWine, mandates that universities eliminate undergraduate programs that consistently graduate fewer than five students per year over a three-year span.

Undergraduate programs being suspended to comply with SB 1:

- Bachelor of Arts in Africana Studies

- Bachelor of Arts in Asian Studies

- Bachelor of Arts in Data Analytics

- Bachelor of Arts in Disability Studies

- Bachelor of Arts in Middle East Studies

- Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy

- Bachelor of Arts in Religious Studies

- Bachelor of Arts in Spanish

- Bachelor of Arts in Women’s and Gender Studies

The programs remain available as minors for students still interested in these areas of study, the university says.

Several other degree programs will be suspended as part of the provost’s review of the recommendations of the Program Reallocation and Investment Committee:

- Bachelor of Business Administration in Organizational Leadership and Management

- Bachelor of Science in Health Information Administration

- Master of Arts in Philosophy

- Master of Arts in Sociology

- Master of Education in Educational Research and Measurement

- Master of Education in Educational Technology

- Master of Education in Educational Psychology

- Master of Music in Music Performance

- Master of Science in Geology

- Ph.D. in Curriculum & Instruction: Early Childhood

- Ph.D. in Curriculum & Instruction: Educational Technology

- Ph.D. in Foundations of Education: Research and Measurement

For more information on the Academic Program Prioritization, visit the university's website.

Ohio’s Reagan Tokes law acts as a ‘one-way ratchet’ for prison time

This story was originally published by Signal Statewide. Sign up for free newsletters at SignalOhio.org/StateSignals. Statewide is a media partner of the Toledo Free Press.

OHIO – In the final month of his two-year prison term, a guard ordered Lamont Clark Jr. into a cramped office.

Against the blurred background of a computer screen, a professionally dressed woman appeared on camera and explained that Clark would not be going home to Cleveland. A new state law required that he spend another year in prison.

The reason: Another incarcerated person claimed that Clark had attacked him in 2023 during a riot at Lake Erie Correctional Institution.

“They never told me who I allegedly assaulted. They just said, ‘Somebody said you assaulted them, and you’re guilty,’” Clark told The Marshall Project – Cleveland this year, after serving the extra time.

This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project – Cleveland, a nonprofit news team covering Ohio’s criminal justice systems.

Hundreds of incarcerated people like Clark are denied release from Ohio prisons each year under Senate Bill 201, better known as the Reagan Tokes law. Tokes was raised in Maumee, Ohio in Monclova Township (near Toledo, Ohio) and graduated from Anthony Wayne High School.

Enacted in 2019, the law was designed to protect the public with a carrot-and-stick approach to incarceration. It gave prison administrators exclusive powers to add time for people who misbehave behind bars, or to recommend early release for those who follow the rules.

But as critics predicted, the law has only led to longer incarceration.

Not a single person has been released early, according to a Marshall Project – Cleveland review of prison records for the past six years. Meanwhile, 700 people — mostly Black men — have been denied release due to added time.

The Marshall Project – Cleveland investigation found no external oversight or internal auditing of administrative decisions to lengthen incarceration. People accused of violating prison rules are not afforded basic legal rights to have access to lawyers, to challenge their accusers or to review evidence.

“When you give this kind of unchecked power to people, it’s going to be abused,” said defense attorney Andrew Mayle, who fought for the law’s constitutionality to be challenged in the Ohio Supreme Court in 2023.

Nearly a third of Ohio’s prison population sentenced under new law

The law was the legislative reaction to the 2017 murder of Reagan Tokes, a 21-year-old Ohio State University student, by a man recently released from prison.

Lawmakers sought to ensure public safety by keeping other potentially violent people locked up longer.

This latest pendulum swing in Ohio’s criminal sentencing laws created a new class of incarcerated people who risk not only solitary confinement and loss of privileges, but also longer prison stays for violating rules. It’s a partial return to the indefinite sentencing that Ohio legislators replaced with fixed prison terms during the popular truth-in-sentencing movement of the mid-1990s.

Under the Reagan Tokes law, judges must again give minimum and maximum prison terms for first- and second-degree felonies.

More than 14,500 people, nearly a third of Ohio’s current prison population, have been sentenced under the Reagan Tokes law.

Critics argue that with no requirement to notify elected judges before adding some or all of the maximum term, lawmakers handed unchecked, extrajudicial power to unelected prison administrators.

Defense lawyers and advocates for incarcerated people had warned that prison officials would likely abuse the power to keep people beyond their minimum prison terms. But they remained cautiously optimistic that the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction might also reward people who follow rules and complete programming by reducing their terms.

But the agency’s reading of the law — choosing a more burdensome requirement for early release — has denied all of the more than 120 petitions by incarcerated people to reduce their minimum prison terms.

Meanwhile, alleged rules violations resulting in added time have amounted to about 830 more years of incarceration, costing taxpayers $32 million based on total operational costs per prisoner.

“This was never pitched as a one-way ratchet, where sentences only get increased and not decreased,” said Matthew Ahn, director of the Beyond Guilt project at Ohio Justice & Policy Center. “…What we have is just another accelerator toward runaway incarceration, toward runaway spending on corrections and imprisonment.”

The law’s implementation also tracks racial disparities that worsen the deeper people move into the criminal justice system. Black men make up less than 7 percent of Ohio’s population and a staggering 59 percent of those given additional prison time under the law. Cuyahoga County is home to just 10 percent of Ohio’s population and nearly 23 percent of those kept beyond their minimum sentences.

Ohio prison spokesperson JoEllen Smith said that director Annette Chambers-Smith “carefully reviewed and considered” each petition for early release before denying them all. Chambers-Smith declined to comment.

The denial of more than 120 requests for sentence reductions hinges on prison officials’ interpretation of the Reagan Tokes law, which established two criteria for early release: adjustment to incarceration or exceptional behavior. Nothing in state law or prison policy requires administrators to pick one or the other before recommending that sentencing judges shave up to 15 percent off minimum prison terms.

State rules define adjustment to incarceration as good conduct, a low security level and no affiliation with prison gangs. Prison administrators, however, say lawmakers set unattainably high standards for exceptional conduct, which include voluntarily completing community service and rehabilitative programming, keeping positive relationships with the outside world and mentoring others.

Critics have maintained all along that, to reduce returns to prison, lawmakers should have addressed the lack of positive programming in prisons.

“The problem with the Reagan Tokes Act has always been that it is more stick than carrot,” said attorney Nicole Clum, who advocated for a more balanced approach as a former legislative liaison at the Office of the Ohio Public Defender.

“If individuals are always given their maximum sentence and never given relief for good behavior, they have no incentive to engage in rehabilitative efforts,” she said. “Ohioans are better served if incarcerated individuals have hope.”

Otherwise, she added, there’s “no reason to engage in rehabilitation. Inevitably, this makes Ohioans less safe.”

Prisons don’t track the reasons people get additional time. So, The Marshall Project – Cleveland spoke to dozens of incarcerated people and reviewed documents in 30 recent cases through a public records request that took officials six months to fulfill. Rule violations for assaults and other sexual misconduct — up 45 percent and 75 percent, respectively, since 2019 — appear to be driving much of the additional time, the limited analysis found.

Prison administrators could not say whether the threat of longer sentences under the Reagan Tokes law might counter rising levels of violence in Ohio prisons. One official suggested that the law would have to apply to half of Ohio’s prison population in order to study its effect.

Those punished by the law describe being locked up with cellmates who violently lash out during mental health episodes or while abusing drugs.

Lifers with little or no chance of parole extort money and commissary funds from people marked by Reagan Tokes sentences. They’re easy prey, some men said. If they fight back, they risk more time in prison. Their aggressors know that, so they pay up or take their beatings.

“Somebody with life said they were going to stab me because we kept arguing. … So, I had to punch him. I had to defend my life in those circumstances,” said Edward Navone, who is spending an extra year at a maximum-security prison in Lucasville after correctional staff found him guilty of assault.

The new law isn’t just impacting prisoners, but taxpayers as well.

Some sentenced under the law say they are denied basic due process protections

When lawmakers introduced the Reagan Tokes Act in 2017, prison officials told the legislature that additional costs would be minimal if sentencing courts accepted their recommendations to reduce sentences for good behavior. But no such recommendations have been made

Instead, Gary Daniels of the Ohio ACLU more accurately predicted what would happen when he testified in a 2018 committee hearing on the proposed bill.

“Under a more realistic scenario, (the law) will dramatically increase our prison population by hundreds per year for the next several years,” Daniels said.

Former Ohio Sen. Kevin Bacon and Rep. Jim Hughes, Republicans who co-sponsored the Reagan Tokes Act with state Senate and House Democrats Sean O’Brien and Kristin Boggs, said any law is worth revisiting.

Bacon said he was “surprised” to hear that all requests to reduce prison terms have been denied.

“I’m hoping that it’s a case where … if it is imbalanced, it’s imbalanced to protect the public,” said Hughes, adding that the state is “dealing with the worst of the worst.”

Boggs and O’Brien are now judges. Neither would talk publicly.

The law provides no checks on how public or private prison staff allege and investigate misconduct, or determine guilt. There’s no external oversight and no annual auditing.

Disciplinary decisions made behind closed doors by appointed members of the Ohio Parole Board may be appealed to lawyers who work for the state prison system. But documentation from those decisions is exempt from public records laws. Judges, who would be required to approve early release, have no say in whether time should be added. They’re not even notified.

“Certainly the judge should have a say if you’re going to be held over,” said Mayle, the defense attorney who argued against the law.

Mayle said he could not think of a political or legal reason for removing judicial oversight other than to give unilateral authority to state prison officials.

“But then again, prisoners are not a very influential body politic. They are easy to dump on,” Mayle said, adding that “there is an economic incentive for people who work in the prison business, whether they work for private or public prisons, to have prisoners.”

Those most affected by the law say they’ve been denied basic due process protections.

Clark, like other men accused by fellow prisoners of rioting at Lake Erie Correctional Institution and later given extra time, was found guilty under a veil of legal and literal darkness.

A power outage hit the privately owned and operated prison in August 2023. The lights and camera went dark when the backup generators failed. Concerned for their own safety, correctional officers abandoned their patrols inside pitch-black pods.

With no surveillance footage or official witnesses, investigators relied solely on confidential sources — other incarcerated men — to identify the alleged rioters and swiftly move them into solitary confinement cells.

Until then, Clark had a clean disciplinary record. But investigators never asked him what happened the night of the riot. Instead, he and others received nearly identical conduct reports from the same investigator. Each report referenced confidential statements as the only evidence against them.

One incarcerated man told officials he was with Clark “all night and he never touched anyone.” It didn’t matter. Disciplinary records show that administrators believed the confidential sources.

Clark was loaded onto a bus as waves of men left Lake Erie Correctional Institution for higher-security and more violent prisons. As their scheduled release dates neared, one by one, they received their extra time.

Dozens of incarcerated people told The Marshall Project – Cleveland that the law’s lopsided rollout and its empty promise of rewarding good behavior had left them demoralized.

“It is frustrating,” said Jose Padilla III at Belmont Correctional Institution. “People get discouraged. When they find out they’re not getting out, that’s when they get a ticket (or rule infraction). People just give up. What’s the point?”

Several men said violence breeds violence. Fists and weapons are survival tools. More prison time doesn’t deter their use when people are threatened with physical harm or worse.

“They put a lot of people in bad situations and expect them to be angels,” said Clark, who was finally released from the notoriously violent Lebanon Correctional Institution in January after serving his extra year.

The Marshall Project – Cleveland also spoke to dozens of people who appear to meet the minimum eligibility requirements to petition for early release. At least four, including two who filed after being contacted by a reporter, were denied for reasons that included the crimes for which they are serving time.

“It just says past criminal history,” James Fleming said of the denial letter he received in June.

Fleming said he’s had no tickets in his three years of imprisonment. He’s been trusted with a maintenance job at Belmont Correctional Institution, a minimum security prison in southeast Ohio. He said he wants to better himself and atone for his mistake.

“I’ve done pretty much any programming I can get into since I’ve been in here,” Fleming said.

Several men said they did not previously know that they could ask for reduced sentences. Others were discouraged from applying by staff.

“I could never get anyone here to help me fully understand it,” said Padilla. “So, I gave up on trying to get what paperwork I would need.

“I’m not saying I’m not sorry about my crime,” he continued. “But I do want to get out and better my life. That’s what I’ve been working on in here.”

Signal Statewide is a nonprofit news organization covering government, education, health, economy and public safety.

Don Lee: RIP Pope Francis

Pope Francis, leader of the Roman Catholic Church and pope to the people, dies April 21 at the age of 88.