Some young Ohioans are unable to drive legally, limiting their job options and ability to participate in extracurricular activities. But some are pushing to return driver’s ed to schools

This story was originally published by Signal Statewide. Sign up for their free newsletters at SignalOhio.org/StateSignals. Statewide is a media partner of the Toledo Free Press.

By Andrew Tobias | Signal Statehouse

Homer Weekly realized the state had a big problem around 2017, when the private driver’s ed school he ran with his wife in Morgan County started seeing students from places farther and farther outside his small southeastern Ohio community.

“We were getting students from Westerville,” Weekly said, referring to the Columbus suburb 90 miles away. “Parents told us their kids were on waiting lists of over 90 to start driving lessons. That’s when we knew it had become a crisis.”

This type of training used to commonly be provided by high schools. But Weekly, a retired educator, opened his school in 1993, shortly after state lawmakers privatized the industry.

Today, Weekly works for a new, fast-growing school-based driver’s ed program based in Zanesville. It’s on the cutting edge of an effort by Gov. Mike DeWine and others to try to revive public driver’s ed.

In interviews and public comments, state officials and advocates describe a failed privatization effort, particularly for rural and poor urban areas. The result has been a system with limited enrollment slots, high prices and slim profit margins for operators.

In turn, many 16- and 17-year-old Ohioans are unable to drive legally.

This limits their job opportunities and their ability to participate in extracurricular activities. It also places them at a higher risk for crashes if they get their licenses after they turn 18 without driver’s ed, according to a state-funded 2022 study conducted by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania. Of course, kids do get behind the wheel regardless.

Ohio officials said of the 113 fatal crashes in 2023 that involved teenage drivers, the teen driver lacked a license or permit in 23 percent of those crashes. Ohio officials don’t track exactly how many teens are unable to access driver’s ed. But advocates and people in the industry are aware of the problem.

A different state-funded study completed in 2023 by the same researchers found that teenagers who live in poorer neighborhoods around Columbus were four times less likely to complete driver’s education than others.

“It’s a huge, huge problem, even for families that have the ability to pay for access to it,” said Kristy Amy, chief of programs for Future Plans, a Geauga County-based nonprofit that works to fight poverty in Appalachian Ohio.

How driver’s education works – and doesn’t work – in Ohio

In Ohio, there are two paths to becoming a licensed driver. One applies to 16- and 17-year-olds, who must get 24 hours of classroom instruction — this increasingly is being offered online — and eight hours of in-car training before they can get their license, among other requirements.

The other applies to everyone 18 and up, who must simply pass a driving test and a written exam and undergo a test of their eyesight.

For new drivers under 18, education options can be limited, either because of affordability, or, in the case of rural areas, physical proximity.

Quantifying the problem is difficult. Ten counties in Ohio — Adams, Brown, Harrison, Monroe, Morgan, Noble, Paulding, Pike, Vinton and Wyandot — have no schools offering driver training, according to the state government’s list of licensed providers.

But state officials say their records may not capture the true picture, since the records may just show the providers’ corporate headquarters and not any ancillary facilities, and since schools may offer driver training in a wide area.

Still, advocates and industry officials say there’s clearly a widespread problem in two types of communities – poorer, urban areas where many residents can’t afford driver’s education and in rural areas, where people can’t afford driver’s education and may not have a nearby option.

“Driver’s ed’s expensive,” said Mike Belcoure, manager of driver’s education for AAA Alliance Inc., one of Ohio’s major AAA clubs. “There’s no better way to put it. It is expensive and it prices, unfortunately, some people out of the market.”

AAA Alliance’s in-car driver’s training instruction, based in and around Cincinnati, Columbus and Dayton, costs $650 per student, Belcoure said. Depending on the market, prices can range as low as $400 and as high as $950, he said.

Families face a waitlist for driver’s education classes

Another issue is waitlists. State law requires students to complete driver’s education within six months. So a student who completes classroom training must also be able to quickly find a driver’s training school with availability.

But the waitlists lengthen for providers further away from major cities, he said.

“You go out to the eastern part of the state, it becomes tough. There are, we call them in the industry, driver’s ed deserts where the supply’s just so low, it is hard for students to find,” Belcoure said.

AAA is a nonprofit, member-owned cooperative, and driver’s education is part of its mission. But for mom-and-pop, for-profit operators trying to get started, starting and running a driver’s training school is a difficult proposition.

Major costs for driving schools include buying and insuring vehicles, and hiring instructors who are willing to get in the car with inexperienced teenage drivers. Some schools were forced to close during the coronavirus pandemic and haven’t reopened.

This explains why private schools are more likely to be available in big cities, where they can count on higher volumes of students.

“Driver training is a difficult business model,” said Kimberly Schwind, assistant director of the Ohio Traffic Safety Office, part of the Department of Public Safety. “Instructors don’t get paid a lot. So it’s difficult to find instructors. You need instructors to find kids. If you pay instructors more, you have to raise prices more. And it’s already too high for most families. It’s a difficult situation.”

One major rural driver’s education business, Capabilities Inc., is able to meet its bottom line in part by doing work for the government. The company, which is based in Saint Marys with satellite locations around the western, central and southern part of the state, does a significant amount of business by offering training to developmentally disabled adults, which makes it eligible for local and state funding.

Owners Bill and Karen Blumhorst say their company also offers traditional under-18 driver’s training for $450 in Saint Marys because they’re committed to their community.

But, in the roughly 25 years their company has been in business, “There definitely are times we’ve discussed, is it financially prudent to keep on providing the service?” Karen Blumhorst said.

DeWine calls for expanded driver’s ed requirements

Despite the existing system’s limitations, DeWine late last year announced he’d like to change state law to require all new drivers, and not just 16- and 17-year olds, to go through driver’s ed before getting their license.

The proposal got some wider news coverage due to issues faced in Springfield, where a mass influx of Haitian migrants has introduced a large number of drivers who are unfamiliar with U.S. driving laws.

DeWine has taken other steps in the past couple of years to address driver’s education availability, such as creating a scholarship program targeted at rural and urban areas. State officials say their Drive to Succeed scholarship program spent $3 million paying to put 5,500 students – or about $550 per student – through driver’s education.

At a Springfield City Commission meeting in October, DeWine’s public safety director, Andy Wilson, said the governor and Ohio First Lady Fran DeWine met with insurance industry executives in the summer of 2024 to discuss the plan to boost driver’s education requirements.

After commission officials raised concerns about the price of driver’s ed, Wilson acknowledged the lack of existing access. He said it traces back to state officials’ decision to move driver’s ed out of public schools in the early 1990s.

“The state privatized it. And when they did they radically altered the model, they radically altered accessibility, and they radically altered capacity. So yes, there is a problem.”

In recent comments to reporters, DeWine said he’ll be talking to lawmakers about ways to expand driver’s ed access soon, possibly via the state budget bill he’s planning to release next week.

“This is something I think that is very needed. There’s a lot of, I think, support for that out there. So we’ll be talking more to the legislature about that in the months to come,” DeWine said.

A possible blueprint to expand driver’s ed opportunities

The new driver’s education program that Homer Weekly runs in Zanesville could offer a blueprint for how the state will approach this issue.

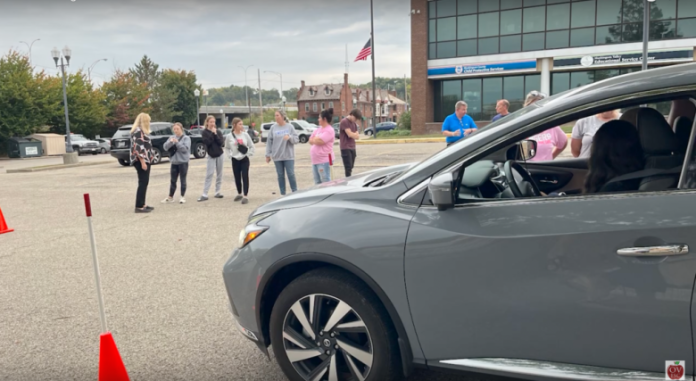

Weekly works for a public school-based driver’s education program called the Muskingum Ohio Valley Educational Service Center Driving School that’s supported by two different education service centers, government agencies that provide support services to local districts.

Local education service officials launched the program in October 2022 using federal coronavirus relief money. The program has expanded thanks to a $1 million state grant in January 2024, awarded by the DeWine administration as part of the state effort to expand driver’s training options.

Weekly and his colleagues run what amounts to a franchise model for driver’s ed. Four core employees administer the program from offices in Zanesville and Cambridge, handling money, developing curriculum and hiring, training and evaluating drivers, among other responsibilities.

Students pay $350 — the very low end of the market price range. And participating school districts provide state-approved driver’s education, including in-car instruction.

Its handful of employees include Weekly, who is a former assistant principal and school athletic director, and Richard Hall, a former superintendent at the Mid-East Career and Technology Centers in Zanesville.

Program leaders say in-school driver’s education solves some of the major problems private providers face.

First, direct government subsidies allow them to charge lower prices. Schools also can roll a major driver’s ed expense — vehicle insurance — into their existing fleet insurance for their school buses.

Schools also help provide a pool of motivated driving instructors, in the form of teachers, bus drivers, cooks and other school employees. Two-thirds of the program’s instructors are school employees, officials said.

They also provide a centralized point to pick up kids and are able to more easily work around the students’ academic schedules.

The biggest burden the driving program poses, program officials say, is the cost of buying cars.

“We have schools in this area that do not offer driver’s ed through us. They stay out of the driver’s ed business, and I think they don’t understand how easy it is for them,” Hall said.

The state grant has allowed the program to grow rapidly. It began with 13 school districts, but today covers 30 districts in 18 counties ranging from Oxford near Cincinnati to the Toledo area.

“I think, you know, it’s just going to catch fire, just like anything else, that it’ll be in almost every school in a couple years,” said Eastin Lewllyn, an official with the Muskingum Valley Educational Service Center that helps runs the program.

The growth has happened with no real advertising, program officials said, and little news coverage.

Program officials say that some private providers aren’t thrilled with their expansion, viewing it as the government competing with and threatening their livelihood.

Private driver’s ed providers recently organized a trade group called the Ohio Driving School Association. The group didn’t return messages.

But officials at the Muskingum Ohio Valley Educational Service Center Driving School believe in their model, saying it prioritizes education, not profit.

“We’re fortunate by our model and being educationally based. If a kid needs something, we don’t need to charge you for it. We have enough resources to do that,” Hall said. “A small school doesn’t have that.”

Signal Statewide is a nonprofit news organization covering government, education, health, economy and public safety.