TOLEDO – Sparsely populated with furniture bolted to the floor and a grayscale palette, the waiting room for the Domestic Relations Court at 429 N. Michigan St. is quiet.

Attorneys speak privately with their clients in soundproof rooms with glass dividers, while others sit in silence, waiting to go before the court.

Present in the sea of waiting is the woman Norma Ramos-Prater came to see. Ramos-Prater, the Hispanic Latino outreach coordinator for the Lucas County Prosecutor’s Office, embraces the woman with a smile, holds her hand and admires her nails.

“She’s shaking,” Ramos-Prater says, squeezing her hand as a few tears escape the young woman’s eyes. The two of them almost have the same uniform – black dresses, braided hair and grave expressions.

The young woman, whose identity is best left unknown, is seeking a divorce and alleging domestic violence. Ramos-Prater is there to translate, provide emotional support and guide the woman through the process.

On the other side of the room, the woman’s husband is visible, also waiting, but then the judge moves the court date back to reconvene at another time.

The victim’s advocate role within the Victim Assistance Program has been around for a number of years. In 1984, Ohio passed the State Victims Assistance Act (SVAA) in coordination with the federal Victims of Crime Act (VOCA), which set aside funding and resources to help people who have had crimes perpetrated against them.

“The work those men and women do at the prosecutor’s office is nothing less than God’s work,” said Matt Cherry, who learned firsthand how important that work is when he was assisted during a court case by Joan Coleman, a strong leader in Lucas County victim’s advocacy, who died in 2023 at the age of 91.

After an altercation at a party, Cherry, then 16 years old, and one of his friends decided to leave the gathering when “the individual who was throwing the house party ran off his front porch and unloaded on our vehicle. Unfortunately, my best friend didn’t make it.”

With a bullet to his leg, Cherry, now 45, was able to physically heal, but said reliving the experience in court was “devastating.”

Vera Sanders, director of Victim Services for the Lucas County Prosecutor’s Office, spoke from her 28 years of experience, and described the judicial process as “not victim friendly. A lot of the victims don’t understand how to maneuver or how to get through the criminal justice process without that [victim] advocate being there to help.”

Sanders attributed part of the difficulty with of the judicial process to the necessary investigative nature of fair trials.

“It is set up as innocent until proven guilty, and so the defendants have to have rights,” she said, and this means victims may have to relive much of the worst moments of their lives as courts come to their own conclusions.

The other difficulty for victims is understanding and trusting the process involved with the judiciary, a hard task for anyone who isn’t trained in court processes.

“She was there and able to explain things to me and able to console me in a way that was different than what my parents and my family could do because she knew what the events were going to be,” Cherry said of Coleman. “And she knew others that went through the exact same thing I did.”

Unfortunately, not all communities or individuals report crimes, and the Latino community has suffered disproportionately due to a declining trust in law enforcement.

A 2013 survey of Latino populations across counties in California, Illinois, Arizona and Texas showed 70 percent of undocumented immigrants were less likely to report being a victim of a crime than other victims.

“They have the same rights as any human being has,” Ramos-Prater said. “And that’s one of the things that I try to educate everyone that comes to me, to let them know they have rights.”

An article in the Journal of Social Work, also published in 2013, found that the entire Latino population had a declining trust in law enforcement, regardless of immigration status or citizenship.

In an attempt to bridge trust, specifically with the Latino population in Toledo, the Lucas County Prosecutor’s Office, led by Julia Bates, curated Ramos-Prater’s position as the Hispanic Latino Outreach coordinator, a specialized victim’s advocate position designed to help victims who are apt to slip through the cracks within the justice system.

Sanders lauded Ramos-Prater for her work as an advocate and for her ability to reach people.

“She’s actually a lifesaver for that community. There’s nowhere in the Latino community that they’re just not raving about what Norma has done and what she means to that community.”

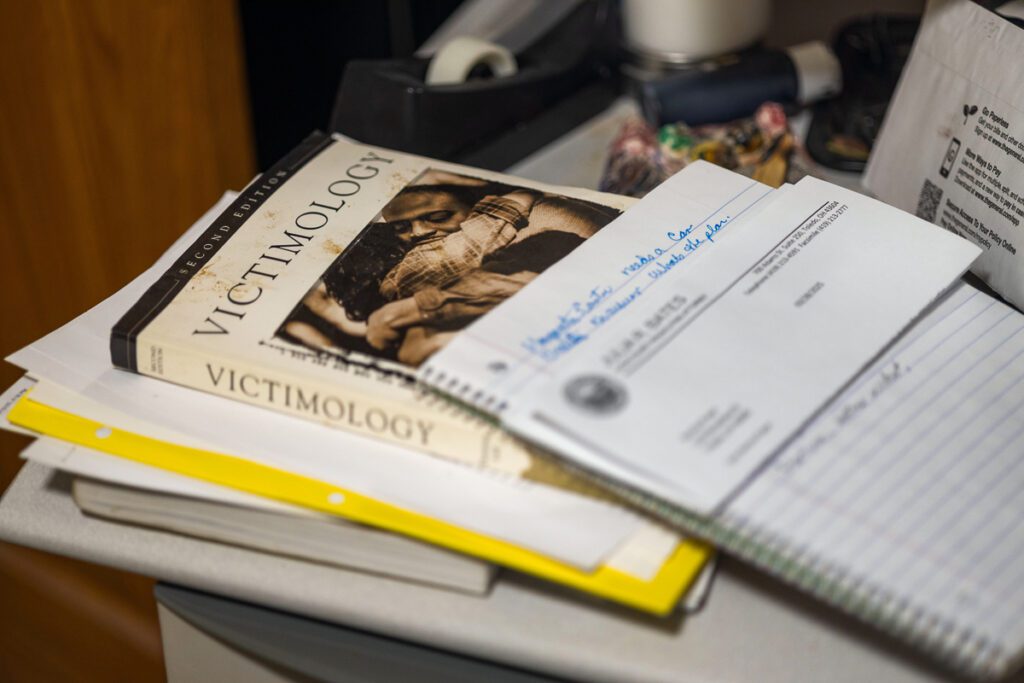

Traditionally, victim’s advocates are tied closely to the court process, but Ramos-Prater also makes herself visible through community events, teaching English and Spanish classes at a local South Toledo Church, and personally familiarizing herself with resources her clients may use in the future.

We don’t trust. They need to see you involved in the community to trust. Sometimes they don’t even give you the right name.

Norma Ramos-Prater

For the past six years, Ramos-Prater has setup her office inside the Sofia Quintero Art & Cultural Center, located at 1225 Broadway St., to make herself available to the community in a less formal setting.

“To get the community involved, you have to get involved in the community,” said Theresa Johnson, an outreach coordinator for St. Lucas Lutheran Church, where Ramos-Prater teaches language classes. Just down the hall from the classes, attendees can also benefit from a free lunch program, free blankets, bookbags, personal hygiene kits, a food pantry, a second-hand store and an Alcoholics Anonymous group.

According to Ramos-Prater, a victim’s main challenges are childcare, language and transportation difficulties, and she does “a little bit of everything,” sometimes beyond victim relief because “the need is so much.”

A woman Ramos-Prater has been helping for years, Mercedes Aguirre, an American citizen living in South Toledo, had problems getting her daughter the medical attention she needed.

“I referred them to the board of disability many years ago,” Ramos-Prater said.

Aguirre’s 15-year-old daughter had complications with a chronic condition and needed help coordinating transportation through the Toledo Area Regional Transit Authority (TARTA), as well as translation for the doctor.

It is small gestures like these, where Ramos-Prater is willing to meet everyday people where they are, in their homes if necessary, and connect them with an array of resources that builds trust within the South Toledo community.

And to keep that trust Ramos-Prater does her homework before she recommends a service or a group to her clients.

“I have to find out which agencies provide services to them, [and] if they are Spanish speaking,” and then, “I act like I’m the one [getting services] to make sure that my victims are not victimized again.

“I went through that free clinic to see how they treated them. And now I know that my victims will get medical treatment at the free clinic and they’re going to be treated properly.”

This is especially important for victims of domestic violence. Ramos-Prater often discovers domestic violence situations tangentially, when an individual needs help with some other service.

Ramos-Prater recalled telling a woman facing domestic violence that she had the right to have a protection order.

“A lot of women don’t know that. They don’t know that they have those rights. Nobody has the right to abuse them.”

The Latino Outreach coordinator is a valued position, and for the moment, is secure for the immediate future. Part of what allows the program to have this added security is diversified funding sources by local, state and federal entities.

Regardless, Ramos-Prater has not been phased by the changes in government, “We’re gonna’ keep pushing forward,” she told the Toledo Free Press. “Our office is gonna’ help victims of crime.”