What one family and nonprofits are experiencing in 2025

TOLEDO – After fleeing Syria and its civil war, Mrs. Alnimer was ready to be reunited with her daughter, Diana Altheyab, in Toledo.

“When they opened the Welcome Corps program I directly applied for my family,” Altheyab said about the finishing touches on the refugee resettlement process she initiated. She expected her mother, sister and brother to arrive in Toledo very soon. “I received the schedule.”

Through a 2023 State Department program called Welcome Corps, five or more U.S. citizens could work with the government to sponsor refugees to be resettled in communities across the United States. Beginning in early 2024, Altheyab organized a number of her fellow U.S. citizens to take the place of a traditional refugee resettlement agency.

“It’s private citizens getting to choose their next neighbors and saying, ‘We want this and we’re willing to flip the bill for the federal government to be able to welcome refugees,’” explained Annie Nolte-Henning, executive director of Community Sponsorship Hub (CSH), a national nonprofit coordinating private sponsorship and traditional refugee resettlement across the United States.

Refugee resettlement, whether private or through an agency, lasts 90 days and involves “ensuring people have housing, getting kids enrolled in school, helping mom and dad find a job,” Nolte-Henning said.

Seven refugees, including three immediate family members and their families, were part of the process started by Altheyab, who raised the money to get her family to safety at the price of $2,375 per refugee, the price as of fiscal year 2023.

Preparations were made for the move to Toledo, including housing and furnishings. And on the refugees’ side, Altheyab’s family began to sell off their belongings in Jordan, where they have been staying as refugees for over a decade.

But what was supposed to be wind in the sails for Altheyab ended up deflating her hope.

“They sent me an email to confirm the money,” she said about the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). And there was one last Zoom call “to confirm that I want them [her family] to come here or not.

“I scheduled [their trip] on the 23rd (of January), then they, they cancel[ed] it the same day,” she lamented. “It was such a shock for me.”

Closed borders

“Overnight and without notice, the entire humanitarian infrastructure that supports newly arrived refugees in the U.S. was dismantled,” said Nolte-Henning. “It was a shock to the system. We were all bracing for something. It just … a stop work order was not what we were bracing for.”

Six executive orders came down from the office of the president on January 20, on President Donald J. Trump’s first day of his second term, locking down the borders of the United States for at least 90 days. Refugee resettlement agencies were ordered to stop their work and roll back provisions and protections for immigrants.

Originally, on the executive orders themselves, these changes were set to take effect on Jan. 27, so Altheyab had moved quickly to get those seven people on a plane to the U.S. before the borders closed.

But without warning, the effective date of the executive orders was moved up to the 23rd.

“My group there in Jordan, they finished everything,” Altheyab said about the long process her family went through to legally and successfully be approved to immigrate to the United States as refugees. The only thing left after the Zoom orientation was booking the flight.

Her mother, brothers and sister were approved as refugees by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), then screened by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), screened by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and then coordinated travel with the State Department, USCIS.

Altheyab said she was so despondent about not being reunited with her family that she spent two days sick in bed. “I was frustrated by this.”

The scramble

The abrupt nature of Trump’s executive orders transitively cut out most traditional refugee resettlement infrastructure by eliminating what the resettlement nonprofits do.

“I lost 85 percent of my workforce,” Nolte-Henning said about her organization, which, in the past, received money from the federal government to resettle individuals.

“The stop work order essentially means that you can’t implement the work, and you cannot charge against your grant to do the work,” so layoffs were the next step.

And then, after downsizing, Nolte-Henning pivoted her organization to help refugees inside the U.S. who had been dropped by their resettlement agencies, and to help Afghans overseas who have Special Immigrant Visas, a program that has not been halted by the Trump administration, yet.

“It’s not just about admissions being suspended, but it has also cut off vital services to refugees who have already lawfully arrived in the U.S,” said Nolte-Henning.

A federal judge attempted to block the complete halt of refugee admissions. The judge said halting all refugee admissions would cause, ”irreparable harms, including refugees stranded after selling their possessions, agencies laying off hundreds of staff, and family reunifications suspended indefinitely.”

Thousands of refugees who came to the U.S. before late January were left without the guidance they would have traditionally received from resettlement agencies.

“So we’re prepared to take on local cases, if needed, of people that are left without case workers or without services that they need,” said Janelle Metzger, executive director and founder of Water For Ishmael (WFI), an English as a Second Language nonprofit (ESL).

Altheyab’s journey: The siege of Homs

Altheyab’s own journey to the United States took four years since she was forced from her home in Homs, Syria.

Luckily, she and her immediate family made it to Toledo in 2016, right before the so-called “Muslim ban.” Before coming state-side, Altheyab lived in Jordan for two and half years, and spent the other one-and-a-half years looking for somewhere safe inside Syria.

Homs was heavily bombed, forcing her and her husband to flee with their children, all five-years-old or younger. Hezbollah, Russia and the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, a fascist relic leftover from World War II, all had documented war activity near Homs.

“I have three baby kids, and we were so young, we were scared, and we had no home,” Altheyab said, recalling the tumultuous time. “We were scared from the killing,” she said, as she told of stories of soldiers forced to kill family members to prove their loyalty to Assad.

Eventually, the violence became unavoidable and began to unfold around the family as resources became scarce.

“So, this car came from Damascus … to sell these groceries,” she said as she began to explain that violence started to break out around the limited commodities of food.

“That’s the day we decided, yes, we have to flee to Jordan, because we had three babies. I had, like five and three and two months [old].”

Refugee living

Under the protection of the United Nations, the couple and their children tried to make the most of a time with little forward progress in sight as they navigated life as refugees in Jordan.

Altheyab did her best to educate her children on her own, providing for them with food while her husband looked for work.

But work was not readily available for Syrians living in Jordan, and Altheyab’s husband was forced to work for rebated wages, with no work protections and no guarantee he would be paid at the end of his work.

“If you are [a] refugee there [in Jordan], you feel like people look [at] you, always, like you are a refugee,” Altheyab said. “As a refugee, you cannot work as you want, you cannot study as you want. People look [at] you, especially in Jordan and Syria.”

“We are a similar culture and similar language, but we also have discrimination,” she said.

The United Nations offered Altheyab an opportunity to go to America, and she accepted. Two and a half years later, after extensive screenings by the UN and the USA, Altheyab, her husband and her three children were able to make it to Northwest Ohio.

Shifting sands: refugee policy in the U.S.

“To be here in America, to be honest, it’s very safe and we have our rights,” Altheyab said. “We feel we are human here, so we decided to come here.”

Soon after Altheyab and her family arrived in the United States, Trump instituted the executive order that halted travel from many Middle Eastern countries, and he specifically barred Syrian refugee resettlement to the United States, blocking the rest of Altheyab’s family from coming in 2017.

Presidents set the number of refugees allowed to enter the United States in a given year, known as the Refugee Ceiling.

The Refugee Ceiling for 2017 was initially set by President Barack Obama at 110,000 refugees, but was cut by over half, down to 50,000 total refugees allowed to enter the United States that year by Trump, the new president.

Over the four years of the first Trump administration, the Refugee Ceiling lowered down to the lowest Refugee Ceiling in United States history, at 15,000 refugees allowed to be resettled for 2021.

When Joe Biden got into office, he responded by hiking the Refugee Ceiling up to 62,500, in May of 2021. But the four years of the Trump administration had already damaged the nonprofit infrastructure responsible for doing the work of resettling refugees.

“We were really undermined, and then you know, it declined from there with our all-time-low under Trump,” said Angela Plummer, executive director of Community Refugee & Immigration Services (CRIS), when asked about how the first Trump administration had affected her organization during that time.

CRIS is a traditional refugee resettlement agency that helps refugees secure housing, find jobs, enroll in school and integrate into the social areas where the refugees have been relocated.

Of the 900 refugees CRIS was set to resettle in 2017, after the changes from the Trump administration, only 300 were able to make it to the United States that year, and their numbers declined each year as the Trump administration continued to lower the Refugee Ceiling.

And even though Biden raised the Refugee Ceiling to 125,000 in 2022, only 25,000 refugees were resettled in the U.S. that year because the resettlement agencies were not able to build back as quickly as they had been cut.

“You can’t just stop and start people,” Plummer said, adding that people stopped years ago had built their lives elsewhere.

The government gives CRIS $1,273 per refugee to spend on that refugee’s behalf, and help them resettle within the first 90 days of the refugees’ time inside the United States.

“It’s not like this is just a government-funded program. It doesn’t work; I mean, we have to find other funds to make sure people can pay all of their rents, especially as I noted, since the per capita amount [the amount of funding per refugee] hasn’t been going up for some time,” Plummer said. “And that $1,273 amount is for all 90 days.”

Plummer said that “it really impacts having an economy of scale. I mean, you can run a much more efficient program at a certain level,” with a certain number of people.

Efficiency and ease of process were not priorities for the Trump administration.

“They threw in new bureaucratic requirements that, in my opinion, did nothing but bog down the system,” Plummer said.

“Instead of refugees having to provide five years worth of addresses, now they wanted 10 years, [and there were] new forms being required…so it’s just putting all kinds of people who had already been screened through the system, like back into a pile of needing to go through security clearances, and things ground to a halt.

“After you had the very overt, ‘we’re not going to allow these people from these countries to come,’ then you had all this stuff behind the scenes, that was kind of the bureaucratic method of stalling.”

Luck of the draw

Just before the refugee system began to get bogged down, Altheyab got in with her immediate family, but the rest of her extended family (mother, father, sister brother) were not so lucky.

An already overburdened and actively undermined system did make room for 6 million displaced Syrian refugees, and effectively stopped Altheyab’s family from uniting with her on U.S. soil.

Biden, in reaction to the rising worldwide refugee population, revitalized a private sponsorship model for resettlement, first with a prototype for Afghans, called Sponsor Circle, then for Ukrainians with the 4UA program, and finally to all formal refugees through the Welcome Corps program in 2023.

Through private sponsorship and Welcome Corps, American citizens were able to partner with the State Department to bring refugees to the United States with private funding.

“So when they opened the Welcome Corps program I directly applied for my family,” Altheyab said.

This was the first time in nearly ten years Altheyab had an opportunity to actively participate in the process of bringing her family to America.

Even though Welcome Corps launched in early 2023, the organization Altheyab went through, Water For Ishmael only got their certification as a Private Sponsor Organization in the first quarter of 2024, and then a year later the program was shut down.

But then, on Trump’s very first day in office, the president put a halt on all new refugee resettlement, and Altheyab’s dreams of reunification were disrupted.

No longer welcome

“We can’t call anything we do Welcome Corps right now, because we did get a cease and desist order from Washington,” said Metzger, who was integral in pushing her organization to receive the Private Sponsorship Organization certification.

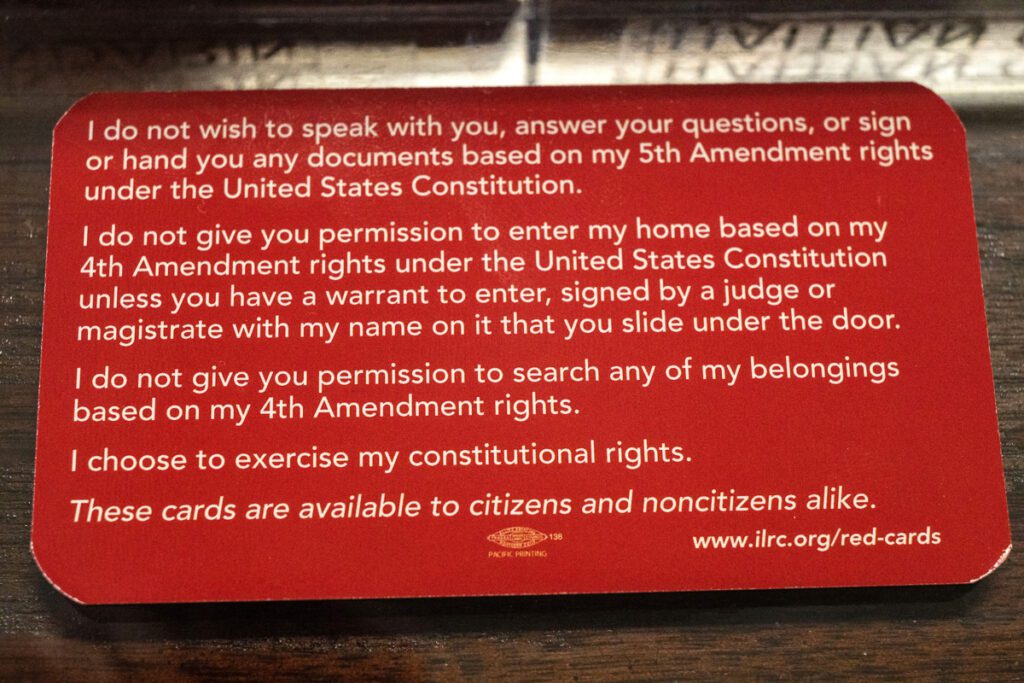

“Right now, the federal government isn’t guaranteeing [that] any refugee who’s already here [in the United States] gets provided the services that they need,” said Scott Andrews, formerly the director of the Private Sponsor Groups, who oversaw the groups of five or more resettling refugees.

Since the interview with Andrews, the Welcome Corps program has been completely dismantled and Andrews works as the director of operations for WFI now.

“The message was simply, ‘You need to stop all work that you’re doing right now,’” said Andrews.

“You can imagine if you just arrived a few days ago as a refugee, you don’t speak the language and you just found out that the accommodation you were promised is gone. You have no place to stay; you have no source of income; you have no job; and you’re just supposed to wander the streets? This is not good for our communities,” Andrews said.

“If this is a money thing [where federal grants are lost], we can sort that out,” Andrews said, but he was unsure if the federal government would forcefully try to stop the organization from helping refugees already in the United States because of the ambiguity of the communications.

Hold please

Even though all refugee resettlement initiatives have been paused with the exception of Special Immigrant Visa holders, technically not refugees, Altheyab holds out hope for her family.

One of the executive orders details that Trump will reconsider allowing refugees into the United States after 90 days from the executive order, April 20, and that is where Altheyab’s hope lies.

After the 90 days, the Secretary of Homeland Security and the Secretary of State will submit a report on “…whether resumption of entry of refugees into the United States under the USRAP (United States Refugee Admissions Program) would be in the interests of the United States…”

“I hope this action can change before the 90 days,” Altheyab said. “Because my family…they sell everything,” in anticipation of leaving Jordan.

“I sent something to Marcy Kaptur [the U.S. Representative from Ohio’s 9th district]. I send every day,” she said about asking for help in getting the rest of her family into the United States.

Altheyab’s mother, brother and sister have been waiting in Jordan for the hostilities to subside in Syria since 2012, and the recent takeover of Syria by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) has not brought a peaceful conclusion to the war.

Revenge killings, massacres of civilians and ethnic cleansing have already been a hallmark of the HTS takeover, and it is unclear if Syria will stabilize its political situation anytime soon.

And it’s anticipated that, at the very least, Trump will significantly decrease refugee admissions.

“I hope Mr. Trump [will] change his mind about bringing refugees, especially Welcome Corps, because it’s our own money, it’s our responsibility, so we decided to bring these people, we know these people. It’s our family,” Altheyab said.