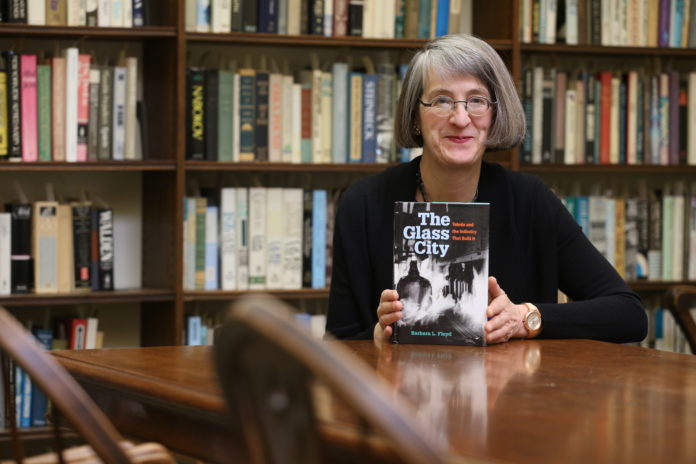

Barbara Floyd spent one year piecing together the history of the business that led to Toledo’s nickname.

In “The Glass City: Toledo and the Industry That Built It,” she follows Toledo’s glass roots from the first fledgling company that fired up furnaces in 1888 to the triumphant reign of three powerhouses — Owens-Illinois, Libbey-Owens-Ford and Owens Corning — that made the town the world leader in glass production, to when that supremacy started to shatter.

“I came away from this project with a new found appreciation for how unique Toledo was in its industrial history — the way the city produced some of the most important developments and technological innovations in industrial history,” Floyd said. “Toledo companies invented the automatic bottle machine, Fiberglas, insulated glass, safety glass for automobiles, structural glass that made skyscrapers possible, glass-composite products and many others.

“In addition, the people who developed new techniques for industrial glass also helped to create the studio glass movement that produced beautiful works of art made of glass.”

A University of Toledo alumna, Floyd is director of UT’s Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections. While writing her book, she utilized Carlson Library’s extensive records on Toledo’s manufacturing glass commerce.

“Beginning in the 1980s, the Canaday Center has been attempting to collect records that document Toledo’s most important industries,” said Floyd, who also serves as university archivist. “The first glass-related collection we acquired was the records of Libbey-Owens-Ford, the producer of window glass. A few years later, we acquired the records of Owens-Illinois, the producer of bottles, and then most recently, the records of Owens Corning, the producer of Fiberglas. These collections represent the most important documentation of industrial glass in the country.”

Knowing that information was stored at UT and that Floyd was the author of several local history works, Scott Ham of The University of Michigan Press reached out to see if she would be interested in preparing a book proposal.

“While there had been historical studies of particular companies in the past, there had not been a comprehensive book that looked at the overall and interconnected histories of Toledo’s glass companies since the 1940s,” said Floyd, who also conducted research at the Toledo Museum of Art, the Museum of American Glass in West Virginia, the Center for Archival Collections at Bowling Green State University and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas.

The history of glass in Toledo all began 127 years ago, when Edward Drummond Libbey moved his New England Glass Company to the shores of the Maumee River.

“Edward Drummond Libbey is arguably the most important person in Toledo’s history,” Floyd said. “Not only did he bring to the city its most important industry, but he also founded one of the most important art museums in the country. And he hired one of the most important innovators in glass technology — Michael Owens.”

At age 10, in 1869, Owens started working in the hot, dangerous glass factories as a “blower’s dog,” the name given to boys who helped glassblowers make bottles.

“I think because of his experience as a child, he began to experiment with a machine to automatically make bottles around the turn of the century,” Floyd said.

By the late 20th century, changes in glass production began to dull Toledo’s once sparkling brilliance. Libbey-Owens-Ford was sold to Pilkington Brothers PLC in 1986, and ongoing asbestos legal battles forced Owens Corning to declare bankruptcy in 2000. Toledo, Floyd noted in her book, was “as fragile as the product it produces.”

Never was that more apparent than when the Toledo Museum of Art’s Glass Pavilion opened in 2006 with large, glass walls that were fabricated in Shenzhen, China. This reflected the globalization of glass production, Floyd said.

“Toledo glass has changed the world. And most significantly, the industry made the city what it is today,” she said. “While the glass industry may play a smaller role in Toledo now, the history between the city and the industry should not be forgotten.”

Floyd will talk about “The Glass City” at 4 p.m. April 16 at the Canaday Center and sign copies of her book, which will be on sale for $30 during a reception after the event.

PHOTO BY DANIEL MILLER / COURTESY UNIVERSITY OF TOLEDO