At least once a week, John M. Heisman is asked if he is related to the legendary football coach.

“I’ll go to a checkout, plop my card down and [the clerk] will say, ‘Oh, Heisman. Like the trophy.’ About 50 percent of the time, they’ll say ‘You’re not related, are you?’ Then I have a decision to make. Do I lie and say no or do I tell the truth and, if they are a sports fan, get into a time-wasting discussion? If I got back all the time I’ve spent answering that question, I’d have another year of my life.”

The answer, of course, is yes.

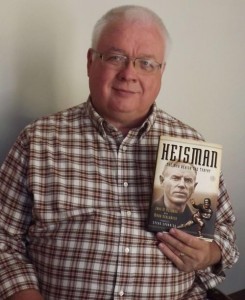

John W. Heisman, for whom the Heisman Memorial Trophy was named, was the Toledo resident’s great-uncle. The trophy is awarded each year to the nation’s most outstanding college football player. Heisman has spent the past several decades researching and writing a book about his relative.

John M. Heisman of Toledo wrote a book about his great-uncle, John W. Heisman, for whom the Heisman Memorial Trophy is named. Toledo Free Press Photo by Sarah Ottney

“Heisman: The Man Behind the Trophy” will be published Oct. 2 by Simon & Schuster. The book was co-authored by ESPN’s Mark Schlabach with a foreword by University of South Carolina coach Steve Spurrier. A prerelease book-signing is set for 2-8 p.m. Oct. 1 at the Ward Pavilion at Wildwood Metropark, 4830 W. Central Ave.

“One of the things we tried to bring out in the book was the fact that his innovation created the American college football game as we know it now,” Heisman said. “There were other contributors — we’re not taking away from them — but he was a catalyst at a critical time in its development.”

Spurrier, who won the Heisman Trophy in 1966, said he was surprised to learn just how much Heisman contributed to the sport.

“Among other innovations, Heisman introduced the center snap, audible ‘hike’ signal, hidden ball trick and lateral passes,” Spurrier wrote. “Much of what Heisman invented nearly 100 years ago is still very much a part of the game today, which is quite remarkable.”

The book was also endorsed by a dozen other Heisman winners, including former University of Michigan receiver Desmond Howard, who won the Heisman in 1991.

“As recognizable as the statue is, many do not know the storied history of the man it was named after,” Howard wrote. “This book explores the life of a legend.”

Coach Heisman played football for Brown University and the University of Pennsylvania, from which he graduated with a law degree.

“He was going to be an attorney, except for an injury to his eyes that kept him from reading for long periods, so he went to his next love — or actually his first love — which was athletics and football,” Heisman said.

His first coaching job was at Oberlin College in 1892. Heisman also coached at Buchtel College in Akron (now the University of Akron), the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Alabama (now Auburn University), Clemson College (now Clemson University), Georgia Tech, which he led to a national championship in 1917, the University of Pennsylvania, Washington & Jefferson College and Rice Institute (now Rice University).

Grades and character were just as important to the coach as playing ability, Heisman said.

“If they used profanity, he pulled them out of the game and sent them to the showers. They were done,” Heisman said. “He expected them to be gentlemen first, football players second.”

Heisman never met the coach, who died before he was born, but remembers a visit from Heisman’s wife, Edith. He grew up listening to his father talk about Heisman, whom the family called “Uncle Bill,” after his middle name, William.

“When Dad wanted to give a lesson in character, I heard a story about Uncle Bill. When he wanted to impart a story of manhood, I heard a story about Uncle Bill. When he wanted me to understand good sportsmanship, scholastic effort or gentlemanly behavior, I heard an Uncle Bill story,” Heisman wrote. “These stories were effective, entertaining and always hit the mark.”

The coach died in 1936. When his wife died in the 1960s, the coach’s personal effects were passed to Heisman’s father. Heisman started going through the papers in the 1970s, but stopped to marry and raise a family before beginning work again in earnest in 2003.

“I went through his trunks and put it all together. It took decades,” he said. “It’s so very surreal [to be finished]. I don’t know that my psyche has allowed me to acknowledge it yet. It feels like I’m still working. I haven’t really slowed down to enjoy this yet.”

Heisman played football for Genoa High School in the 1960s, where he said he was “outstandingly average,” and then played rugby at Ohio State University, experiencing a game much like the college football his great-uncle knew.

“It gave me an appreciation for where the sport came from,” Heisman said. “If you take away Heisman’s contributions, you basically have an orphan-child blend of soccer and rugby … and basically without the fan base we have now. It’s not the game we have now, not anywhere close.”

Heisman said the most surprising thing he learned was how active his great-uncle was in theater — regularly acting in plays as well as managing an acting troupe during the offseason.

“For years he actually made more money on stage than he did coaching,” Heisman said. “He was very shrewd and quite an entrepreneur. This guy went out, sized up opportunities and seized them. That was reflected in his coaching, in his acting and in how he went into communities and picked up sports columns and wrote for newspapers. He was sort of a Renaissance man.”

Although Heisman doesn’t usually attend the ceremony, he said he has become good at predicting the winner.

“I’ve been able to call it for the last several years, probably the last decade,” he said. “There’s only been a few surprises.”

He’s also met many of the winners.

“It would be easier to tell you the ones I haven’t met,” he said.

One of his most memorable interactions was with quarterback Tim Tebow, who won the Heisman in 2007.

“Tim looks you right in the eye. He’s very genuine. He wants to know what you have to say,” Heisman said.

Heisman was 12 years old the first time he saw a Heisman Trophy.

“It was pretty neat, but I’ve never been in awe of it because, if this is a memorial, then basically I’m looking at a tombstone,” Heisman said. “That’s the way I’ve always looked at it. It’s too bad everyone has forgotten what the memorial is for and who they are honoring.”

Heisman said he hopes the book sheds light on the history of football and the man behind the trophy.

“It’s going to give a depth and a richness to the heritage and the tradition,” John said. “I want people to understand a sense of history, a sense of the fact that this game we take for granted was basically a sandlot game back in the day.”

Heisman also hopes the book will clear up his connection to the coach.

“Hopefully I won’t be stopped at stores anymore and asked about my name,” Heisman said, smiling. “That’s my personal reason for writing this.”

For more information, visit www.coachheisman.com.