TOLEDO – Flags bearing the outline of an eagle’s head on a red background waved across Broadway St. was paired with chants to free Kilmar Abrego Garcia during the March & Rally for Immigration Reform, put on by the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC).

Prompted by President Donald Trump’s aggressive approach to immigration, FLOC’s march on May Day, May 3, ended at Golden Rule Park in South Toledo, where a semicircle formed around a trailer hitched to a Ford F-150. Then the rally began.

Garcia, an El Salvadoran living in the United States since 2012, has become a symbolic case for immigration in the United States.

More specifically, Garcia’s deportation without due process to Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo, or CECOT, a massive prison in El Salvador, has sparked national outrage. According to the 5th (federal level) and 14th (state level) Amendments, every person living in the United States, including undocumented immigrants, has a right to procedural due process.

The U.S. Supreme Court has ordered Trump to “facilitate” Garcia’s return, but without visible progress towards the court’s order, the future of immigration appears tenuous.

Short term resolutions

“This is not a new problem for us,” said Baldemar Velasquez, president of the FLOC, before the rally. It’s more prevalent now, because of Trump, but we’ve lived with this immigration threat our whole history.”

Ancillary speakers, like Lucas county commissioner Pete Gerken, spoke before Velasquez about short-term goals, and referred to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers as modern-day Gestapo agents.

“The hottest place in hell is for those, who in a great time of crisis, maintain their neutrality,” Gerken proclaimed, and launched into some practicalities.

“There will be no federal arrests on our grounds or in our buildings!” Gerken assured attendees, and promised he would pass a resolution saying as much. Next, Gerken offered to ascertain the specific charges associated with those “picked up” by ICE and moved to the Corrections Center of Northwest Ohio (CCNO) in Stryker, Ohio, so all the detainees might have due process.

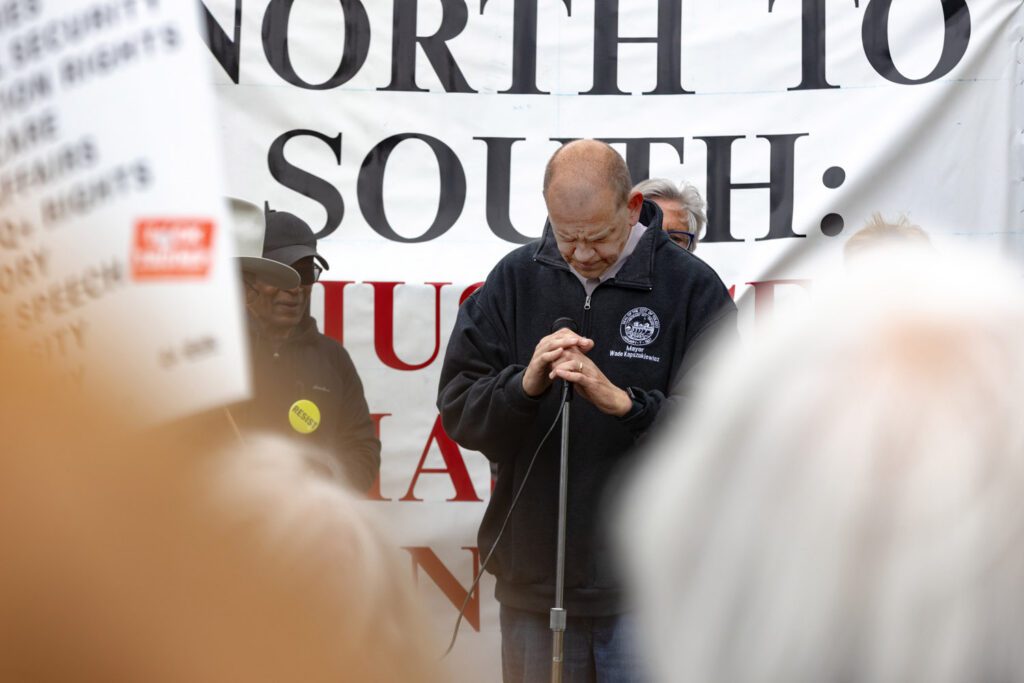

Toledo Mayor Wade Kapszukiewicz spoke to the need for solidarity with migrants who had not been given due process by reciting Martin Niemöller’s poem about the Holocaust “First they came for…”

During the vote to allow ICE detainees at Stryker, Lucas County Sheriff Mike Navarre said of ICE’s actions, “We’re destroying families by deporting parents of children who are here legally. The federal government created this problem, and they have not offered a solution yet, and that’s what I’m waiting for.”

Long-term sustainability

Speaking to the crowd of about 450 people, Velasquez sought to bypass reactive approaches and pointed out the root of America’s immigration problems.

“The issue we need to address here is the issue of labor rights,” he said. “Nobody’s asking why these people are here in the first place.

“They’re fleeing this and fleeing that, but what’s that connected to? That’s connected to our foreign policy and our trade agreements. Workers have to be put in a position where they can negotiate their treatment, their wages and where they’re working to avoid exploitation.”

FLOC handed out flyers with four main points calling for:

- Amnesty for immigrant workers

- Sustainable trade agreements, so people could “support their families without needing to leave their country”

- Expanded worker rights for immigrant workers on H-2A and H-2B visas

- An expanded immigration judicial system to meet the needs of processing immigrants

FLOC and agreements

Across states, across employers and borders, the FLOC has helped agricultural workers by providing protections to associate members.

“When we organize a group of workers that don’t have collective bargaining agreements, we allow them to be associate members. They can come from any type of work: agriculture, construction, roofing, restaurants.

“We have a referral system; if they need an attorney for this and that, in particular if somebody got cheated for not getting paid by a restaurant or something like that, we’ll intervene for them, and act as an advocate for them.”

Velasquez explained a large sticking point for farmworkers is that “we’re excluded from the National Labor Relations Act.” As per the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, agricultural workers do not have the same protections as others do, so the FLOC fills in where it can as an organizing committee instead of a full-fledged union.

“We want labor rights for agriculture. We want mechanisms to be able to have freedom of association, the right to form unions,” Velasquez said.

Chained to supply

The FLOC’s first major campaign started in 1978 when Velasquez organized a boycott and strike of Campbell’s Soup Co., and then implemented their plans in 1979.

“We compelled the company to implement a mechanism for collective bargaining within their supply chain,” Velasquez said when asked about how they were able to get better rights for workers in spite of the government not recognizing their right to organize.

“They [Campbell’s Soup Co] designed this production system. They can design it with labor rights, voluntarily and unilaterally.

Why wait for a law to make you do it?”

Eventually the campaign was a victory, but the strike and boycott took eight years, ending in 1986 with a historic three-way labor deal between the FLOC, representing workers, and then growers and farms that supply to Campbell’s, and, finally, Campbell’s Soup Co.

“You got to include the whole supply chain,” Velasquez said.

Negotiations alone took about two years to formalize, but by the end of the finalized agreement, farm workers bypassed the need for the government to step in.

Under the new agreement, workers could negotiate wages, working conditions, established minimum pay, an incentive system, unemployment benefits, social security benefits, and Velasquez said workers were given Blue Cross Blue Shield health insurance.

“They could take their family to the best doctor, best hospital, best clinic, wherever they wanted, instead of standing in line for handouts from the government,” Velasquez said. “They’re making beggars of our people by creating all these social service programs.

“Hey, if we had a fair day’s pay, we’ll pay for our own food, pay for our own stuff.”

Other major campaigns by the FLOC include Mt. Olive Pickle Boycott (1999-2004) and their current campaign against Reynolds American Tobacco, which Velasquez said was waylaid by the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.

The FLOC has also been successful in making formal agreements with local law enforcement beginning in 2017, when the Black & Brown Unity Coalition (BBUC), the civil rights arm of the FLOC, signed a code of conduct between its members and the Toledo Police Department (TPD).

More recently, in February, the FLOC made a deal with the Lucas County Sheriff’s Office, and signed a code of conduct. These steps are seen as peaceful steps toward police reform across Northwest Ohio.

Punching up

“This is a critical moment for our nation,” said Marcy Kaptur, the longest serving female member of the United States House of Representatives for Ohio’s 9th District, following Velasquez’s words and matching the red flags with a red coat.

“Most of us here, if it were 1789, we would not be citizens of our country,” Kaptur said, likely referencing the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, the law Trump has been using to deport immigrants without due process.

“It took until 1920 for women to be afforded the right to vote…and it took a war in 1865 under President Lincoln to free the slaves. There’s a lot of history here for protecting and fighting for those who work, and work under very terrible, terrible conditions.”

Kaptur started off by saying she opposed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) when it was drafted under George H.W. Bush, and then passed under Bill Clinton. “When we voted on NAFTA, we tried to get a ‘no’ vote, and we knew the people who did this have made so much money because they play off penny-wage labor.

“We’re being led by very selfish, highly wealthy people who have no idea about what your family has done in this country and what you have done to survive.”

In the middle of speaking about the conditions of migrant workers in North Carolina, where many associate FLOC members are located, a member of the crowd disrupted Kaptur’s speech, asking why she had voted for the Laken Riley Act, passed in January, which lessens protections for immigrants and also allows states to sue the federal government for not being tough enough on the border.

An uproar from the crowd silenced the disruption, and Kaptur responded, “I can talk about those…” before the dissatisfaction of the crowd drowned out the questioner, and she said, “Must be on the other side.”

Continuing to speak to the bleak conditions she saw in the tobacco fields of North Carolina she resolved, “I am for the reformation of the National Labor Relations Act, to include agricultural labor, continentally,” which would mean Canada and Mexico would be allowed to organize their labor.

The action on Saturday afternoon marked one footnote in the decades-long resolution of the Farmer Labor Organizing Committee’s efforts for equity among agricultural workers.

“I was so proud of Marcy Kaptur, because she went with me to Monterrey [Mexico] and talked to the authorities in Nuevo León for a fair and honest investigation,” Velasquez said, detailing how one of FLOC’s organizers, Santiago Rafael Cruz, had been bound and beaten to death in 2007 inside a FLOC office in Mexico.

Velasquez was appreciative of the congresswoman, and said without her support, the FLOC would not have had a successful investigation of the murder through the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to give FLOC protective orders.

“We’ve been consistently targeted internally and externally, all over the place,” Velasquez said. “We continue to fight the naysayers and people who don’t get the understanding of the broader framework of how agriculture works and what’s the relationship with everybody.

“Immigrants are in a very vulnerable position, but that’s why we’re asking to reverse the dismantling of the immigration judicial system by expanding and hiring more adjudicators to uphold due process of refugees, societies, parolees and victims of crime.”

The number of FLOC members has dwindled in Ohio over the years, but has grown in North Carolina, where the collective bargaining membership has grown to about 90,000 members.

Velasquez said his next step is to hold similar rallies in other migrant communities where FLOC is more active.

“This is a really hard struggle,” Kaptur added. “And you have to ask yourself, ‘Are you up for it?’”