This is a limited series on farming. The next story will focus on local family farms.

(⚠️ Content Warning: This story contains descriptions of animal cruelty and graphic conditions inside factory farms, which some readers may find disturbing.)

Americans eat a lot of meat. We each eat an average of 116 pounds of chicken, 84 pounds of beef and 66 pounds of pork, annually. To be able to consume as much meat as we do, we rely on factory farms. There are presently 24,000 factory farms that raise approximately 1.7 billion animals in the United States.

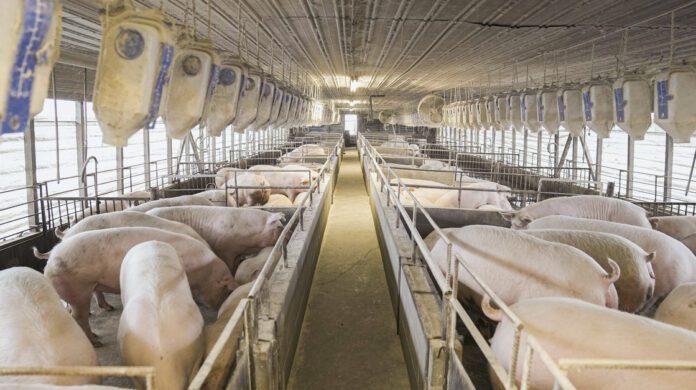

A factory farm is a large-scale facility where animals like cows, pigs and chickens live primarily indoors in crowded conditions. These farms focus on boosting production while cutting down on costs. Factory farms are also called concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs. Here, animals are often kept in tight spaces and raised in bulk to meet high demand.

The EPA’s 2020 report on Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) recorded 257 permitted sites in Ohio. However, the real number could be much higher when considering facilities that operate without permits. Pinpointing the exact count of CAFOs in Ohio remains a challenge. A map of CAFOs in the Western Lake Erie Basin can be found here.

Effect of factory farms on human health

Dr. Kathleen Longo, from Ann Arbor, who is board-certified in internal medicine and worked at the VA in primary care, now volunteers for organizations like the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine and Mercy for Animals. I interviewed Longo about the impact of factory farms on human health.

The first topic we discussed was the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Longo felt that “they use so many antibiotics in the farmed animals because they’re so confined in small spaces that they can get skin diseases and they can get diarrhea, and it passes quickly to the other animals. So, once those antibiotics are used in livestock farming, it promotes the bacteria to become more resistant. And so, then, that’s less antibiotics that we can use for humans.”

We then talked about diseases that can be spread by animals, or zoonotic diseases. Factory farms often crowd animals together and lack proper sanitation. These settings help diseases that move from animals to animals and spread quickly.

Swine flu, avian flu, salmonella and MRSA are found in this type of facility. In fact, about three out of every four new infectious diseases come from animals. Large-scale animal farming has played a significant part in their spread.

In regard to pollution and health, Longo stated that “when you think about the factory farm runoff into the water and into the soil, all their fecal organisms from the animals pollute the surrounding water and pollute the surrounding soil, so that is a chance for it to contaminate the food products, or contaminate a farmer’s field and contaminate your water supply.”

Wastewater runoff can also include nitrites, heavy metals and pesticide residues. These substances have been linked to cancer and reproductive issues in surrounding communities.

Factory farms also release gases, such as ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, into the atmosphere. These emissions can cause breathing problems, including asthma and bronchitis, among workers and people living nearby.

Concerning foodborne illnesses, animals kept in factory farms often face stressful environments, which weakens their ability to fight off infections, such as Salmonella and E. coli. This raises the risk that these bacteria will end up in meat and dairy products. Worldwide, about 35 percent of foodborne illnesses are tied to meat, dairy or eggs from these farming systems.

Working on a factory farm can be challenging. Factory farm workers often experience dangerous job conditions. They face a higher risk of injuries, breathing problems like chronic bronchitis, and mental strain due to weak labor protections.

Negative effect on farm animals

Another source for this story was Dr. Tim Reichard. Reichard served for 22 years as chief veterinarian at the Toledo Zoo and was a member and chairman of the Animal Welfare Committee of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Reichard grew up on a small dairy farm in western Pennsylvania, and, at that time, his family had a herd of 40 cows.

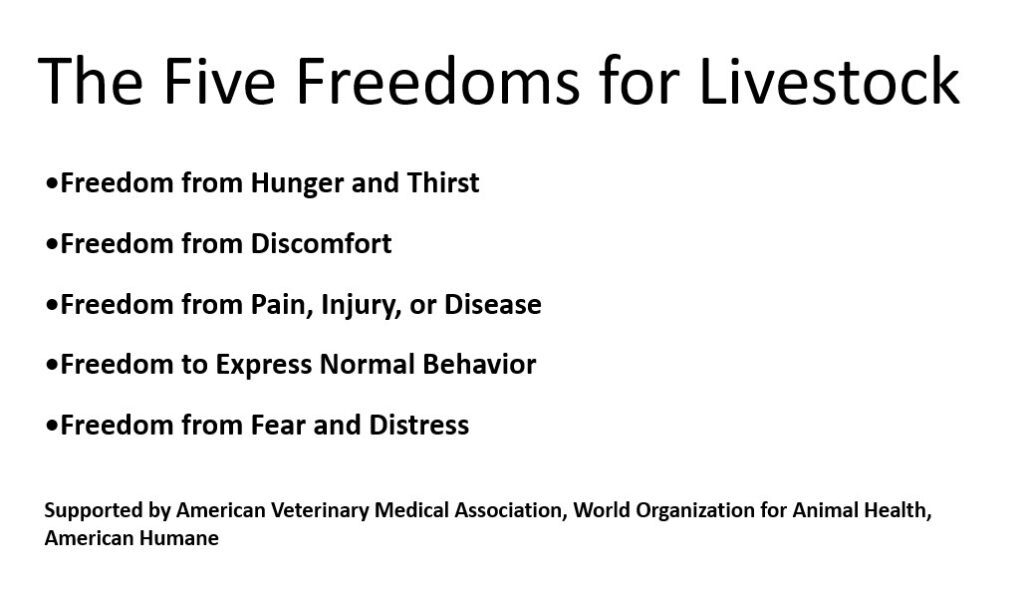

He believes very strongly that animals are not treated well at factory farms. In response to the poor treatment of animals, Reichard focuses on animal rights and promotes the Five Freedoms for Livestock. The Five Freedoms for Livestock (Figure 1) are internationally recognized principles for evaluating and promoting animal welfare.

These guidelines are often seen as the standard for humane treatment and have been adopted by groups like the American Veterinary Medical Association, the World Organization for Animal Health, the ASPCA and American Humane. They aim to guide farmers, veterinarians and policymakers in creating better living conditions for animals while considering the practical challenges of farming systems.

Managing a factory farm involves confining large numbers of animals, such as cows, pigs and chickens, in highly constricted crowded environments, like cages, stalls, barns or feedlots to produce meat, milk and eggs.

In reality, the farming industry often treats animals as if they were unfeeling assets rather than the intelligent, complex and emotional creatures they are. Most of us do not get to know what they’re like since we only know them as meat from the grocery store.

Because of these issues, there is resistance to factory farms across the country. Locally, Lake Erie Advocates, Lake Erie Waterkeepers, Wood County Citizens Opposed to Factory Farms and the Environmental Law & Policy Center have been fighting factory farms for many years.

“When they’re kept in those small areas, and a lot of times they’re on wire, it affects the bottom of their feet – the leg deformities and so forth that occur from being in that environment – they can barely stand anymore. It leads to arthritis,” Reichard said.

Confinement of animals on factory farms

Extreme confinement is a characteristic of factory farming that leads to boredom, frustration, stress and other serious concerns.

As Reichard mentioned, hens raised for egg production are often kept in battery cages – small enclosures made of wire. Each hen is given a floor area equal to the size of a sheet of printer paper, and the cages are usually about 15 inches tall. This small space prevents the birds from fully spreading their wings without hitting the cage walls or other birds. As a result, these cages restrict nearly all of a chicken’s natural behaviors, such as dust-bathing, nesting and scratching.

Cattle raised for beef often begin life grazing on open land, eating a traditional diet. This period ends around one year of age when they are taken to the (CAFOs). These facilities are densely packed indoor spaces, where cattle are fed mainly corn until slaughter. The overcrowding, poor sanitation and low-quality feed contribute to significant health issues. There is an increased risk of bacterial infections, prompting the routine use of antibiotics and hormones. These are used to maintain health and ensure the cattle reach the desired slaughter weight.

Most pigs raised for meat production in the United States live indoors in confined, overcrowded facilities.

Pregnant sows are commonly kept in gestation crates for their four-month long pregnancies. These cramped enclosures are so small that the animals can only stand or lie down and cannot turn around. As well as limiting movement, these crates deprive the sows of mental and physical stimulation.

Shortly before giving birth, sows are moved to farrowing crates. These enclosures are also restrictive, with the added restriction of little contact between mother pigs and their piglets, except for nursing. Once the piglets are weaned, the sows are re-impregnated and go through the same cycle of confinement and stress, repeating this process until they are sent to slaughter.

“With swine operations, it’s concrete or mats or whatever, because you have to have a method to clean them out,” said Reichard. “And being in that situation, it leads to a lot of a lot of arthritis, and just if you can imagine where you can barely, barely move around.”

Also concerning to Reichard was that “chickens and pigs kept inside could be seriously overheated without adequate cooling in summer temperatures.”

Painful procedures on factory farms

Animals are often subjected to painful procedures while they are kept in overcrowded conditions, including during transport. When animals retain their beaks, horns or tails, they may unintentionally or intentionally injure one another. To prevent this, practices, like dehorning cattle, trimming chickens’ beaks and docking the tails of pigs, are carried out. These procedures are typically done without providing any form of pain relief.

Cattle are treated at an early age to prevent horn growth. For very young calves, disbudding (removing horn-producing cells) is done by using a hot iron or caustic paste before horns begin to develop. Reichard prefers that the caustic paste not be used since it can run into calves’ eyes. When the horn tissue has attached to the skull, cutting through the bone (dehorning) may be required. Disbudding is usually preferred over dehorning as it is less invasive, carries fewer risks, and is less painful. Even disbudding can cause prolonged pain lasting weeks or months.

Farmers disbud or dehorn cattle to reduce the chances of horn-related injuries. Horns can cause bruising during transport and pose risks to other animals and handlers on the farm.

Historically, tail docking has been performed on pigs, sheep, dairy cattle, and cattle reared on feedlots with slatted floors. The procedure has fallen out of favor with cattle.

Pig producers commonly dock tails to reduce the risk of tail biting and chewing among pigs in shared pens. Tail biting can be problematic because it can cause infection, reduce weight gain and increase the need for veterinary care.

Tail docking is typically carried out within the first week of life, often along with other procedures, such as castration, teeth clipping and ear notching. In piglets, scissors, sharp instruments or a hot knife are often used to remove most of the tail.

Beak trimming, also called debeaking, is performed on chickens raised for laying eggs and breeding stock used for meat production. The procedure involves removing a portion of the beak using either a heated blade or a high-intensity infrared light. Typically, between one-third and two-thirds of the beak is removed.

The primary purpose of beak trimming is to decrease the pecking of feathers, wattles and combs. According to Reichard, the debeaking is also done “because chickens in confinement will go after each other if there’s a little bit of blood, so they can kill each other.”

One of Reichard’s frustrations is with the USDA Animal Welfare Act (AWA), enacted in 1966, that addresses animal well-being. It is the primary federal law in the United States regulating the treatment of animals in research, exhibition, transportation and commercial sale. The act addresses housing, handling, sanitation, food and water, veterinary care, exercise and psychological well-being, except for farm animals. Reichard expressed great concern that the USDA Animal Welfare Act does not cover farm animals used for food or fiber.

In summation, factory farming treats animals inhumanely by overcrowding, forcing animals to live in uncomfortable environments and performing painful procedures to make them more manageable. Factory farming also poses serious risks to human health through environmental contamination, disease proliferation, antibiotic resistance and zoonotic diseases.