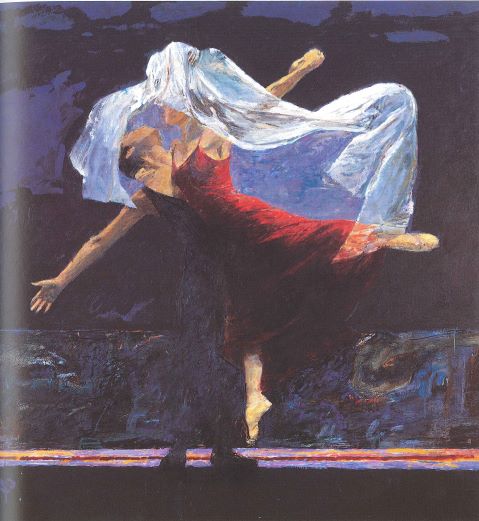

Some of Robert Heindel’s dancers look as though they might peel themselves off the canvas to dance before your eyes. Loosely laced to thickets of hues and shapes, the figures compose their own nuances of sorrow and joy, love and attraction.

It’s typically not their faces that tell the story — for their features are often vague and blended — but it is the motion of their bodies that speaks, paused forever in a quiet universe where the beauty of the human condition is the only thing that matters.

You might hear the dancers’ whispers because Heindel labored over capturing each of their emotions and personalities when he painted them. He got to know them and stood in during rehearsals to study every move.

“He got under the skin of the person he was looking at,” said Colin Rawlings, Heindel’s former agent. “If they were having a bad day, you could see it in the drawing.”

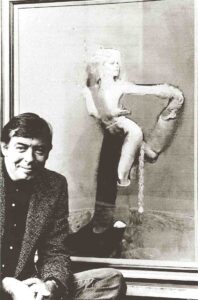

Heindel’s work is permanently on display at the Smithsonian Institution, the Glasgow Museum and the National Portrait Gallery in the United Kingdom, and elsewhere. Before his death, his paintings sold for as much as $55,000; now they’re selling for the equivalent of $130,000 in the U.K., Rawlings said.

Heindel palled around with princesses and dignitaries, sold paintings to Princess Diana and become a household name among Japanese royalty during his life.

“He’s America’s best-kept secret,” Rawlings said. “He’s celebrated in Japan, he’s celebrated in Europe, but for one reason or another, America never really got it.”

And here’s a little-known fact: The late ballet-painting superstar was born and raised in Toledo.

Toledo exhibit

Heindel and his wife Rose moved away from Toledo after they married and started having children, but Rose and at least 30 of his paintings are making the trek home for a show starting July 18. Sur-Saint Clair, at the corner of Washington Street and St. Clair Street, will feature a range of Heindel’s artwork and many of them will be for sale, said Richard Rideout, who runs the gallery with his wife, Janet Albright.

The opening will commence with a 5 p.m. VIP reception, in which major donors will be able to meet Rose. The gallery opens to the public at 7 p.m. and the exhibit will continue through July 20, running from 7-9 p.m. There is a $5 fee to help cover expenses incurred by shipping paintings from all over the country, Rideout said. If you miss the show, you can call the gallery and make an appointment to see Heindel’s work July 21 and 22.

Rideout said he first saw Heindel’s art at a friend’s house in Florida. He was struck with Heindel’s ability to capture motion.

“His story is extremely intriguing and being from Toledo — and there’s the fact that he’s got all this fame and notoriety and talent and I’d never heard of him before and no one else in Toledo had really,” Rideout said.

The Beginning

Heindel was born to a single mother at St. Vincent’s Hospital in 1938. He was then adopted by a couple who could not have children. He started drawing at an early age, stealing time between classes at Central Catholic High School to jot down illustrations. But he also had another love at a young age: Rose.

She was attending Libbey High School but her sister, who went to Central Catholic, introduced Robert to Rose when they were in their early teens. Young Robert asked her out multiple times, but Rose’s parents wouldn’t let her date him until she was 16 years old. By then, the two were inseparable.

Heindel’s parents didn’t have the money to send him to art school, so he took correspondence courses through the Famous Artists School during high school. The East Coast-based company would send him assignments and he would complete drawings and send them back for judging.

The couple married shortly after high school graduation and they later moved to Akron. Shortly thereafter, they moved to the Detroit area, where Heindel put his modest training to work for an ad agency, drawing up advertisements for new car models that ran in print media.

But he wanted to go farther.

“I remember one day in the late 1960s, they lived in Detroit and were moving to Westport, Conn., and he said he needed an agent, someone in New York City that was privy to the illustrator world,” said longtime friend Jim Fisher.

“The next thing I know, a year or so later, his work is on the front cover of TIME magazine — and that was during the Watergate years!”

For TIME, Heindel sketched a portrait of Daniel Ellsberg, who released the controversial Pentagon Papers. He also sketched covers for Redbook and Ladies’ Home Journal.

Heindel knew, even as he was breaking into the commercial art world, that he wanted to eventually foray into fine art. But it wasn’t until Rose convinced him to join her at a ballet that he figured out how to get there.

Rose had always wanted to take ballet lessons as a child but her parents could never afford it.

“I wanted to go to the ballet and I remember saying ‘Why don’t we do this?’ and he did not want to do it,” Rose said. “He finally said ‘OK,’ and that was the beginning.”

International success

From then on, Heindel introduced himself to ballet troupes, earning their trust and spending hours watching the dancers rehearse, snapping pictures at just the right times.

“He rarely painted them in the performance,” recalled his son, Troy Heindel. “He thought that painting them while they were rehearsing was a more true reflection of the person because once they were out in front of the audience, guards went up and people were less exposed.”

Troy had two brothers: Todd and Toby. Troy said their images frequently made their way into his father’s paintings after long modeling sessions before a camera. But you’ll seldom see three boys together in Heindel’s renditions: He’d make Troy out to be the girl in the trio.

Heindel’s first big exhibit was in 1979, at the American Illustrators Gallery in Atlanta. The following few years he set up shows in Missouri, Texas, Washington D.C., California and Cincinnati. Then, in 1984, he made his big break in London at The Stables Gallery, followed by shows at The Royal Opera House and the Royal Festival Hall.

It was that show that landed him an opportunity to work with one of the theater’s most noted luminaries: Andrew Lloyd Webber. The composer saw his work at the hall and immediately asked Heindel if he would paint scenes from “Cats” and “Phantom of the Opera.”

Heindel’s resulting work is haunting: many of the Phantom pieces are laden with dark colors and

ghost-like figures that smear themselves across the canvas while leaving a heavy and frenetic afterglow.

A book called “Moving Pictures,” which celebrates Heindel’s life and works, describes Heindel’s “Jellicle Ball” painting as a “ferocious surge” from “Cats.”

“A mass of humanoid felines, cuddly and murderous, furry and psychotic, just baying for blood,” the book reads. “And that one pair of focused black eyes behind the marmalade hair, stares straight into yours. Stare back and you are lost.”

Heindel continued to paint ballet, garnering attention from the royal family in England, particularly as Princess Diana bought more of his pieces.

Rawlings said Heindel fans are drawn to the allure of his subjects.

“There’s a sexual charge in much of the work — it’s very subtle but it is there,” Rawlings said. “There are not many forms of art where you can legitimately go and enjoy bodies.”

But Heindel’s paintings took a turn when tragedy struck.

Somber paintings

His son, Toby, was diagnosed with cancer. He had been living in Los Angeles, working to become a movie director. He died in 1990 at 30 years old. Troy said his father’s way of working through the loss was to paint, and in his grief he created pieces that differed from much of his previous work.

“They’re very somber paintings,” Troy said. “One shows my brother’s head, and his beautiful face, and below the cancer is eating him up.”

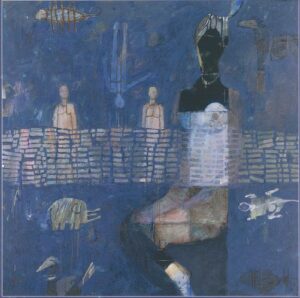

Shortly after Toby’s death, Heindel helped design the set and costumes for a performance called “The Dance House,” which centered around the AIDS epidemic. The paintings portraying the performance are dark.

“The performance was sad … there are a lot of scary pictures in it that are about death and life,” Troy said.

But Heindel’s first major collection of work after Toby died consisted of paintings under the “Penguin Cafe” title. These paintings covered a ballet by David Bintley about endangered species. The dancers in Heindel’s pieces are wearing animal suits; one of his subjects stands off-kilter in a penguin suit, carrying a tray of drinks in a seemingly haphazard way. Another painting shows a human in a zebra costume blending into the back end of an actual zebra, twisting with pain.

Toby’s death also inspired the painter to call upon memories from a vacation to Africa that he and Rose had taken before Toby’s death. African wall paintings suddenly resonated with Heindel and he started creating his “Painted Wall” collection — his first and only images that were not born from dance or theater.

The “Moving Pictures” book quotes Heindel’s reflection on his wall paintings:

“The art is so primal, so basic to the human condition, that Toby’s death started to fit. They may look to the casual observer as mere decoration, but I hope people will recognize that there’s something more. I can’t stop painting figures, but I needed to paint these abstracts.”

Fear of rejection

Also somewhat different from Heindel’s typical ballet paintings are his depictions of noh and Kabuki, traditional styles of Japanese theater and dance. Some of these paintings contain no bodies or faces — just costumes and masks. These paintings were displayed multiple times in Tokyo and a couple of times in Nagoya. Members of Japan’s royal family purchased Heindel’s artwork, Rawlings said.

But, if you haven’t heard of Heindel, you’re probably not alone.

“He didn’t want to be rejected in his own country,” Rawlings said. “He couldn’t bear the idea of having a major show in New York City because he was so insecure in the fact that, in his home ground, he might get deflated and that is such a pity.”

Heindel hosted only one New York show and set up most of his U.S. exhibitions in California. During his initial shows in the states, he could never sell enough to make him feel as though he had succeeded, Rawlings said.

Heindel wasn’t out for the money; he judged success on sales because of his background in commercial art. When he started out, he could only make a living if he got his illustrations printed, Rawlings said.

The Rose stamp

Heindel died in 2005 after doctors diagnosed him with emphysema. Rose came home from running errands one day to find him inside his running car, within the closed garage.

“We had an amazing life,” Rose said. “He was on machines and he couldn’t work. He had to go around with oxygen [tanks] on his body and he just didn’t want to live like that.”

He was 66 years old.

Rose holds on to a number of her late husband’s paintings — especially the piece he completed after a trip to the beach. He took some photos of Rose walking in a wraparound cloth and later painted the image. This was one of his first pieces that wasn’t intended for commercial sale, she said.

Whether a painting portrays Rose, she is still present in nearly all of Heindel’s work in spirit. Heindel’s signature was a rose stamp, as a subtle symbol of adoration of his high school sweetheart.