By Sarah Ottney and Danielle Stanton

Toledo Free Press Managing Editor, Toledo Free Press News Editor

sottney@toledofreepress.com, dstanton@toledofreepress.com

When a toxin was detected in Toledo’s drinking water last week, triggering a do not drink advisory affecting up to half a million people, it was called a crisis, a disaster and a nightmare.

It’s also being called a game changer, a tipping point and an eye-opener.

Toxic algae in Lake Erie is not new. Scientists have been studying it for decades and environmentalists and politicians have been raising the alarm for years, only to be largely ignored.

Western Lake Erie Waterkeeper Sandy Bihn is one of those who has been pushing for action.

“This is like my worst nightmare, not being able to drink the water,” Bihn said. “But maybe it’s an opportunity to find the solutions we need.”

Last year, Carroll Township in Ottawa County issued a water advisory after detecting unsafe levels of microcystin in its water; the same toxin caused Toledo’s issue.

“After Carroll Township, I thought there would be major changes, but there were not,” Bihn said. “That was the first time in Ohio, but [Toledo] is kind of the unthinkable — a major city. That was 2,000 people; this is half a million. I’m hoping the scale will begin to inspire the changes we need. We need to keep the pressure on.”

RELATED: VIDEO: Experts address Lake Erie’s toxic algae at forum

RELATED: Water coverage: Toledo makes national headlines

RELATED: City asks residents to conserve and reduce water usage for algae season

A microcosm of Lake Erie is Grand Lake St. Marys State Park in west-central Ohio, hit hard by algae the past three years, resulting in lost tourism, recreation and business, Bihn said.

“The thing about Grand Lake St. Marys that people should look at is … year after year it’s gotten earlier and worse. So once this stuff gets in your watershed it seems to be a devil to get rid of,” she said.

Lake Erie, the shallowest and warmest of the Great Lakes, is the most susceptible to algae blooms and the “dead zones” they can cause.

Algae growth peaked in the 1970s, when measures were taken to control the problem. By the mid-1980s, phosphorus loadings had been reduced by more than half and the lake’s recovery was a globally known success story, according to a report released in February by the International Joint Commission.

However, by the early 2000s problems with excess nutrient enrichment appeared again in Lake Erie, and have continued to worsen.

Algae has again been a major issue in Lake Erie since about 2003, with the worst year in 2011.

The blue-green algae that can be seen lapping many of western Lake Erie’s beaches is called cyanobacteria, which contains the toxin microcystin. When the cyanobacteria dies it splits apart, dumping its toxic load, referred to as lysed. Whole, or unlysed, cyanobacteria is still dangerous to drink because it will break open during digestion.

Municipal sewage plants were the primary sources of phosphorus runoff into Lake Erie in the decades leading up to the 1970s. Today, it comes mainly from “nonpoint” sources, such as runoff from fertilized farm fields, over-applied manure, lawn and garden activities, construction activities and more, all exacerbated by natural effects like sunlight, warm temperatures, rainfall and more.

Both natural and chemical fertilizers contain high levels of phosphorus, which encourage growth of crops — and algae. One problem today, Bihn said, is that there are still excessive levels of phosphorus found in sediment, so even if new runoff could be held to zero, there would still be algae problems in the lake for years.

“In many cases we just don’t have good data,” Bihn said. “We really don’t know where we’re at or how much we’re gaining or losing on this problem. We really need an annual report card.”

New technology

One local company that could help find a solution is Blue Water Satellite, a startup founded in 2009 in Bowling Green and now based at the University of Toledo’s LaunchPad Incubation Program. CEO Milt Baker said he agrees with Bihn that a report card is needed, but points out one already exists — in the form of satellite images.

n National wildlife federation President and CEO Collin o’Mara points to an algal bloom in Western Lake Erie near the city of Toledo’s Water intake facility. Toledo Free Press photo by Sarah Ottney

Baker and his team use patented algorithms to extract digital data embedded in satellite images to track phosphorus and the growth of harmful algal blooms. Similar technology is utilized by the federal government, military and some universities, but Baker believes Blue Water is the only for-profit company using it.

Satellite images over the past 20 years show western Lake Erie getting “nothing but worse,” he said.

“We’ve tried a lot of things and now is the time to try new things because Lake Erie treatments have not produced the results that people expected,” Baker said. “We need to start looking at new technology.”

The goal is early detection and efficient sampling. The traditional method of scooping a water sample and testing it at a lab gives researchers a single data point; looking at a satellite image offers 200,000 data points per satellite sweep, Baker said.

“What we say we’re doing at Blue Water is we move the lab to the sky,” Baker said. “Five to 10 years from now no one will ever do it that way.”

Unlike many other countries, testing for microcystin is not mandated by the state or U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

“You have to give Toledo credit because a lot of these water bodies are not even looking for the toxin,” Baker said. “In America we only react to crises. We don’t worry about prevention. It was always a theoretical thing that the toxins could get in the water and we might have to shut the water down.

“Now you have a major metropolitan area with 500,000 people that can’t use water. That’s a totally different perspective. So I think things are going to be completely different from here on out. I might be totally wrong, but I think as a result of this we’re going to see federal regulation and we’re going to pay a lot more attention to it.”

Environmentalists

National Wildlife Federation President and CEO Collin O’Mara happened to be in Michigan near Lake Huron when Toledo issued its water advisory. He decided to check it out for himself.

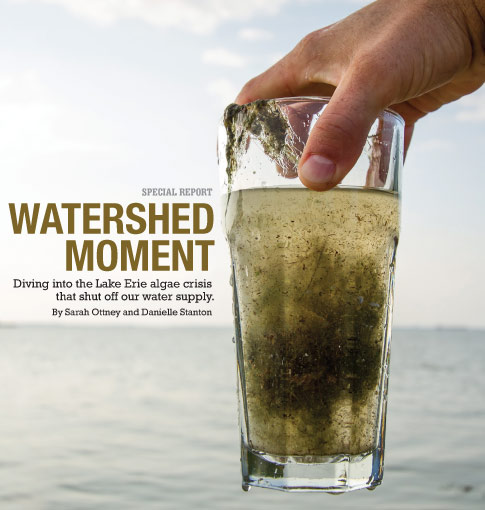

On Aug. 3, he and Bihn took a boat three miles off shore to Toledo’s water intake facility, where he examined a glass of water scooped from the lake, thick with green algae from top to bottom. Such stratified algae can’t simply be skimmed off the surface, making it more complicated to clean up, O’Mara said.

Bihn said she was surprised the algae was so thick so early in the algae season, especially considering that July was cool and dry.

“If it was 100 degrees I don’t know how we would deal with that,” Bihn said. “Boy, when it explodes in hot temperatures, that’s a scary thought. We really need to get ahead of this.”

Toledo’s recent crisis was caused by a perfect storm of excess nutrients exacerbated by environmental conditions.

“There’s a systemic challenge that we face here in the Great Lakes that’s actually much bigger than this one crisis,” O’Mara said. “And unfortunately, this crisis could just be the tip of the iceberg unless we begin to address it.”

O’Mara said although algae is a known problem, it can be hard to predict or control.

“The turning points can happen fairly quickly and all of a sudden you’ll see these fairly broad explosions, where you kind of hit a tipping point and then all of a sudden you have a challenge,” he said.

Bihn called Lake Erie’s algae a “warning sign” for the other Great Lakes, which sometimes appear healthier because they are deeper and appear bluer.

“What happens here will happen to the rest of the Great Lakes,” Bihn said. “Here, the lake turns over every 2.6 years. Other lakes are like 75 to 100 years so once it gets there it’s really too late. If we can solve the problem here, they can get ahead of it.”

To have a freshwater drinking supply impacted so extensively by something other than a single industrial disaster is rare, O’Mara said.

“It wasn’t a single facility that failed that caused this event. This is a series of individual decisions over many, many years,” he said. “The work we do today isn’t going to actually solve this problem overnight. It’s going to take years of this work to try to reduce the amount.

“If we don’t get a handle on these problems, folks are going to start having questions about whether it’s safe to enjoy the incredible recreation that is all around us in Lake Erie,” he said.

“It’s going to be a huge challenge that Toledo can actually lead on,” O’Mara said. “What you do here in response to this crisis could become a bit of a national model. Folks are struggling with these algae challenges in a lot of places. If we can figure out how to solve this issue right here in Ohio we can create a model that can be replicated across the country.”

Timeline

The first inkling something was amiss started with an elevated microcystin reading at Collins Park Water Treatment Plant between 5:30 and 6 p.m. Aug. 1. Although the reading of 0.6 microgram per liter was still within the acceptable level of 1.0 microgram per liter for safe drinking water, the city contacted the Ohio EPA, which advised more testing. That test came back around midnight and the city issued a do not drink advisory around 1:30 a.m. Aug. 2.

In all, about 500,000 people were affected by the advisory as Toledo’s Department of Public Utilities provides drinking water to 125,000 residential, commercial and industrial accounts in Lucas, Wood, Fulton and Monroe counties.

Around 9:30 a.m. Aug. 2, Collins said additional tests had been ordered and urged residents to remain calm.

At 11:40 a.m., the Toledo-Lucas County Health Department recommended restaurant and food facilities using city water close. Throughout the day, amid reports of price gouging and bottled water shortages, water distribution points were organized by both public and private entities.

At 9:15 a.m. Aug. 3, Collins announced test results were still delayed. “Factual info will be relayed when we have it,” he posted to Twitter. Ohio Gov. John Kasich arrived in town that afternoon.

Throughout the day, test results were promised and then delayed with little explanation, causing frustration for many residents. At 3 a.m. Aug. 4, Collins said two of 30 tests came back “too close for comfort.” He said the two could be anomalies, but wanted to be sure and wouldn’t “isolate part of the city” by lifting the advisory for anyone until he was sure it was safe for everyone. The two areas were later reported as East Toledo and Point Place.

“The majority of areas are satisfactory, but we still have two spots of concern,” he said. “I’m not going to take any chances with this community’s well-being and health.”

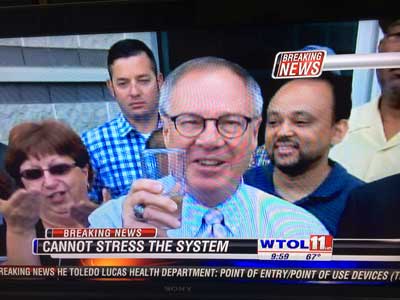

At 9:30 a.m. Aug. 4, Collins announced the final tests had come back clean and the advisory was lifted.

“Our water is safe,” he said, before sipping a glass of tap water. “Here’s to you, Toledo. You did a great job.”

New standard

Toledo City Councilwoman Lindsay Webb, chair of the Utilities & Public Service Committee, said the advisory forced city, state and federal officials into “uncharted scientific territory.”

“Before this happened there was no agreement on how to accurately test for this toxin,” Webb said.

Collins said the Ohio EPA, the U.S. EPA and other agencies were initially “territorial.” Each used its own testing methodology, yielding different and confusing results, he said, but in the end they came to a consensus for a standard test, which will now be implemented throughout the state.

“I’m absolutely convinced we have set the stage for what will now be the state standard related to how to test for this particular toxin as well as laid the foundation for what I believe will be pending USDA regulations related to his particular toxin,” Webb told City Council on Aug. 4.

“Unfortunately, it took a disaster to get us to that point,” said Department of Public Utilities Director Ed Moore.

The two-and-a-half-day situation cost the city an estimated $207,000, said City Finance Director George Sarantou, which includes $73,000 for Department of Public Utilities overtime pay, $52,000 for Department of Public Services overtime pay, $48,000 Toledo Police Department overtime pay, $10,000 in Sheriff’s Department overtime pay and $10,000 to fly water samples to Cincinnati, Columbus and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula for testing. [Editor’s Note: City’s estimated cost has been updated with new figures.]

That’s not including costs from the Ohio Department of Transportation, the Lucas County Sheriff’s Office or the cost of flying samples out of the city to testing sites in Cincinnati, Columbus and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

Lucas County Health Commissioner Dr. David Grossman said reports of illness Aug. 2 were “a little elevated but nothing outside the ordinary,” but quickly returned to normal levels.

Between Aug. 2-5, Mercy and ProMedica health systems reported a total of 229 cases of nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, although hospital spokespeople said it’s not possible to conclusively link the cases specifically to water ingestion.

On Aug. 4, the Lucas County Commissioners started the process of applying for government aid by retroactively declaring a state of emergency for Lucas County. If approved, local governments and businesses could be reimbursed for costs.

Commissioner Carol Contrada sees the crisis as a timely “window of opportunity” to restart discussions among jurisdictions about ways to make the regional water system more efficient and equitable.

“We have several proposals that have been developed and haven’t really been seriously looked at by all the participants because they are relatively new,” Contrada said. “There have been a lot of other things that have taken precedence, but now this is a very timely report.”

On Aug. 5, officials announced one of the Collins Water Treatment Plant’s six flocculators — paddles that mix water drawn from Lake Erie with chemical treatments — was broken. Moore said the damage occurred after the water advisory was lifted and played no role in the advisory. He also insisted the damage was not caused by stress on the system after the advisory was lifted.

Political response

Lucas County Commissioner Pete Gerken called the water advisory a “clarion call.”

“The plant wasn’t the problem; the lake is the problem. We have not for a decade collectively, as a country or a community, addressed the assault on Lake Erie that’s been going on,” Gerken said. “If this isn’t a clarion call … I don’t know what is.”

Rep. Marcy Kaptur, whose 9th Congressional District stretches for 141 miles along Lake Erie’s coastline encompassing Toledo, Port Clinton, Sandusky and part of Cleveland, agreed.

“It’s a wake-up call because it alerts people across the entire region as to the condition of our lake and how we are all connected to it — our lives depend on it,” said Kaptur, a ranking member on the House Subcommittee on Energy and Water.

The water intake facility for the City of Toledo is three miles off-shore in Lake Erie. Toledo Free Press photo by Sarah Ottney

One solution Kaptur advocates: Push more money into the Western Lake Erie Basin (WLEB) partnership. The partnership is a conservation group formed in 2006 by the USDA and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers comprised of local, state, regional and federal groups who track the Lake Erie watershed and look for solutions to its problems.

The WLEB partnership needs more funding, political power and authority to carry out its work, Kaptur said. The partnership could use more water monitoring devices, for example, that track the flow of water. When the flow is reduced, algae blooms grow.

Kaptur said she has told state officials, including Kasich, about the WLEB partnership and the need to expand it; however, the governor has a lot of catching up to do, she said.

“He doesn’t come from this part of the state, so we have a lot of learning to do,” Kaptur said.

Kasich said the state will conduct an investigation into what happened in Toledo, which includes taking a look at the city’s aging water treatment system and figuring out how to reduce pollution that feeds the algae in the western end of Lake Erie.

Asked if Kasich planned to sponsor any new legislation in light of the recent crisis, press secretary Robert Nichols wrote in an email: “The governor always refers to Lake Erie as Ohio’s crown jewel, and as such, we have implemented a number of new, strict policies to better protect it. When it comes to the lake, we remain vigilant, and as we do our after-action review of the events in Toledo, we’ll be looking for any new ways and ideas to continue to improve policies that impact the lake.”

Sen. Rob Portman talked to reporters during a conference call Aug. 4, five hours after Toledo’s no drink advisory was lifted. He said the first step toward a solution is to identify how elevated toxic levels entered Toledo’s water supply in the first place, calling for more federal oversight and continued cooperation among all levels of government.

Portman then pointed to a bill he co-authored last year, the “Harmful Algal Blooms and Hypoxia Research and Control Amendments Act of 2013,” which calls on federal agencies to make Lake Erie algae blooms a “priority,” from monitoring and research to reduction efforts.

“This legislation takes critical steps toward protecting Lake Erie and Grand Lake St. Marys from harmful algae that has become a tremendous problem for fresh water bodies in our state,” Portman said last year. “For the first time, we will prioritize the protection of Ohio’s fresh bodies of water, which is critical for our tourism and fishing industries.”

Portman called on the EPA and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to develop an action plan to foresee, control and reduce the algae blo

oms. He said NOAA has the ability to use satellite technology to view the algae and could use this technology to predict and prevent the algae blooms as well as pin-point cause and effect.

“It can be a bipartisan issue,” Portman said. “It’s a complicated issue. That’s why it’s critical we have the very best science to come up with the best information on why these blooms are happening. And that we are using the right technology.”

Asked whether there would be any additional federal regulation, Portman said there needed to be further study.

The federal government may be passing legislation and looking at the problem, but that isn’t enough, some local officials have criticized. Collins’ administration has come out shouting that higher-up officials have been making promises they haven’t been able to keep in regards to cleaning up the lake.

“I don’t think it’s any question that this crisis has elevated the concern,” Ohio Sen. Randy Gardner said in response to the criticism. “People have a right to be frustrated and upset about what happened and we need to answer every question and do everything we humanly can to see it doesn’t happen again.”

It’s still unclear how microcystic toxins showed up in Toledo’s water supply and those questions need to be answered, Gardner said. In the meantime, he is investigating whether other plants in the region need to improve their systems to prevent a similar crisis.

A day after the advisory was lifted, Gardner visited treatment plants in Sandusky, Oregon and Port Clinton. People are still asking the question, ‘Is my drinking water safe to drink?’ he said.

“It’s not all about Toledo: We’ve got Oregon, Carroll Township, Huron, Sandusky, all within my Senate district. We need to care about every treatment plant,” Gardner said.

If there is a way to test lake water before it reaches the intake to the treatment plant we should be doing so, Gardner said. That would tell us sooner whether the water has toxins from an algae bloom and treatment could begin. Gardner is currently working with the EPA to provide funds to treatment plants so they can afford such preventative testing.

In January, state lawmakers unanimously passed Senate Bill 150, which aims to reduce the amount of nutrient runoff that is a major cause of algal blooms. Farms of 50 or more noncontiguous acres would have to get state certification to apply chemical fertilizer. However, the rules laid out in the bill will not be mandatory until 2017 and it does not regulate manure as a fertilizer on frozen ground.

State Rep. Michael Sheehy tried to introduce an amendment that would have acknowledged manure as a fertilizer, but there was no support for it and it failed to pass, he said. Sheehy hasn’t given up, though, and is currently looking for a co-sponsor.

“Green” farmers have been cooperative and responsive with limiting the amounts of fertilizer they use; however there are some “bad actors” out there, Sheehy said. So-called CAFO farms — concentrated animal feeding operations — are the biggest culprits, he said.

“It’s like a farm factory — enormous amounts of pigs and chicken,” Sheehy said. “They’re trying to maximize the number of product that can be developed on the minimum amount of land and resources. One of the byproducts is a bad thing — it is excess amounts of manure.”

Western Lake Erie Waterkeeper Sandy Bihn, left, and National Wildlife Federation President and CEO Collin O’Mara with a glass of water scooped out of Lake Erie in the heart of the algae bloom near the City of Toledo’s water intake facility three miles off short. Toledo Free Press photo by Sarah Ottney

Rains wash manure into the water basin and from there into Lake Erie, where algae forms. It’s a problem that has been identified but these farms have not been cooperative in reducing their manure, Sheehy said.

A decade ago, many officials wouldn’t acknowledge phosphorus caused the algae blooms, Sheehy said. Now, committee heads are meeting to address the issue and Sheehy believes something big will come from it.

“State government is going to do something very serious and very effective and very long-standing to correct the phosphorus load in the Maumee River region,” he said.

“This crisis has brought into focus for people in this region how fragile Lake Erie is, and simply put, you can’t continue to abuse the lake when you depend on it as your lifeblood,” said Kaptur spokesman Steve Fought. “This didn’t happen overnight but by the same token we have no reason to believe that it will markedly improve overnight. It’s like that Joni Mitchell song: ‘You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.’”

Toledo City Councilman Larry Sykes said there have been a lot of questions and “balls in the air” since the advisory. Mayor Collins plans to form a committee, Sykes said, but the issues are nothing new.

“How long have you been talking about it? Twenty years? And it hasn’t rung a bell?” Sykes asked Sheehy on Aug. 3. “I think that bell has been rung.”

Sykes said Toledo has been “ducking a bullet” for years.

“We have known for 20 years or more that we’ve had a problem with our water system and algae. We’ve known that,” Sykes said. “I go back to a couple years ago, we tried to address this problem then and [Council] was voted down. [Former Mayor Carty] Finkbeiner fought with the EPA and the city lost and we were forced to go out and build a new water system. We’ve been dealing with water for God knows how long now. If we had looked at this earlier, it would have been less costly.”

The city is approaching the final leg of a $521 million sewage project called the Toledo Waterways Initiative. The initiative began in 2003 after a decade of litigation between the city and the federal government for Clean Water Act violations. The violations are against the city for decades of sewage spills into the Maumee River, Ottawa River, Swan Creek and other tributaries that feed into western Lake Erie.

Sykes said a big problem is the antiquated system in Toledo. Collins Park Treatment Plant is at least 80 years old, he said.

While acknowledging the issue is a difficult one, Collins promised he wouldn’t let it drop.

“This is not the simplest of all issues. It is a problem that is really created by a variety of things. There’s no one simple answer to it,” Collins said. “It’s going to take the best science, it’s going to take the best engineering and it’s going to take political will. I can’t, seven days from now, look back over at this weekend and say, ‘That was then and this is now,’ and go on to my new problem. This is my problem and I fully intend to engage.”

But environmentalists like Bihn and O’Mara hope politicians do more than just talk or haphazardly allocate more money.

“This isn’t just passing a law or finding a little bit of money, this is actually having folks across the region think about the contributions they are making,” O’Mara said. “A lot of these folks might live miles away from the water itself but that extra fertilizer you’re putting on to get your grass just the right color, that’s contributing to this problem.”

Farmers

No one disputes runoff from farms is one major cause of algae growth. However, many farmers, like fourth-generation Northwest Ohio farmer Todd Kapp, 27, were left feeling “a little aggravated” by online commentary during the advisory blaming farmers alone.

Most farmers strive to be environmentally responsible, said Kapp, who farms with his father Robert and brother Joe in the Curtice area.

“Why would a farmer want to waste their hard-earned money by ‘dumping’ fertilizer into the ditches?” he posted to his wife’s Facebook page Aug. 4. “Lets not just blame the farmers here. EVERYONE including the farmer, city guy and everyone in between needs to step up and help fix this problem.

“Our farm has been soil sampling for several years,” Kapp wrote. “We variable rate our fertilizer and place [it] where it needs it. We plant cover crops, we use no-tillage practices when we can. We do not spread fertilizer or manure on frozen ground. I am not saying every farm does this, however every farm has the opportunity to work with local soil & water conservation district like we do to implement better practices on farms.”

Reached by phone, Kapp said his livelihood is tied to the land so he wants to protect it and preserve it for the fifth generation, including his 2-year-old son.

“Some aren’t as aggressive with it, but I’d say in general everyone is trying to do their share,” Kapp said. “There are a few farmers that still fertilize [with the old methods] and aren’t into the cover crops. They don’t see the benefit, but maybe this will help open their eyes.”

Mike Libben, district program administrator with Ottawa Soil and Water Conservation District, said he’s seeing growing interest from farmers in conservation programs.

One of the easiest methods to reduce farm runoff is the USDA’s Lake Erie Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program.

The program pays farmers to plant grass filter strips and buffers next to streams, rivers and drainage ditches on their property, creating a border between fields and water, he said.

In the past, farmers would apply a blanket amount of fertilizer to the whole field, sometimes enough to last several years. Today, variable rate technology — a process by which soil samples are taken and fertilizer applied only where needed — is rapidly becoming a standard procedure.

“Instead of putting 200 pounds of fertilizer across the whole field, you put only 25 pounds here, 300 here or nothing here,” Libben said. “It’s like a prescription for the field.

“Five years ago, it was a retailer here and there, but in the last few years it’s really ramped up and everybody’s using that technology. We’re definitely seeing more interest.”

The Western Lake Erie Watershed extends from Fort Wayne, Indiana, to the west, Sandusky Bay to the east, Findlay to the south and three lower Michigan townships to the north. It encompasses 6 million acres of land drained by the Maumee, Portage and Ottawa rivers, as well as the open waters of Maumee Bay.

“For farmers here around the lake, [conservation programs are] an easy sell,” Libben said. “The farther away from the lake, it’s out of sight, out of mind. They don’t have as close a tie as we do.

“If we held back every drop of fertilizer, we’d still have algae bloom. That sediment is in the lake already. Those conditions are already there. It’s going to take some time for the lake to heal itself,” Libben said. “Zero percent [runoff] will never happen, but we can do everything possible to minimize that. It’s been a wake-up call that we need to make some changes and do some work.

“I just want people to realize farmers aren’t doing anything intentionally. They are doing things they were taught over the years. Sometimes it’s just something else we need to be taught about and learn and change.”

The future

Could the crisis happen again?

“It’s not debatable. It absolutely could,” Moore said. “This is Mother Nature we’re dealing with. There is nothing we could have possibly done different that would have prevented this.”

Blooms will remain a threat until algae season is over, typically by late September. Officials have asked residents to use water conservatively until then.

“The slower we process the water, the greater the opportunity we give the chemicals that are involved to clean it out,” Collins said. “I don’t want to go through this again so I have to take a step of prevention in order to create a pound of cure.”

The city has increased the amount of activated carbon and chlorine added to water and is currently testing daily for microcystin. All levels have been undetectable.

The challenge will be fixing the problem, not just the symptoms, Gerken said.

“We can fix pipes. It’s going to take a whole lot of people and some time to fix a lake. And that’s where we’ve got to go now,” he said.

Everyone agrees making forward progress will require teamwork.

“The idea that any single entity can solve this problem is simply wrong,” O’Mara said. “We’re all going to have to do our part to get at these challenges and I’m absolutely confident the good people in this part of Ohio can come together and do just that.”